Various Remix Videos and Mashups

Image source: still of Dave Chapelle impersonating Rick James from “Mashup Video with Jackson, Britney & Rick”

The following is a set of links I prepared for one of my classes on film and video language. I repost them here for later use, and to share with the online community. The list is not by any means exhaustive, and is not linear in any way. The top links are mashups and the bottom links are early hip hop and rock videos. They were chosen in part because of the different approaches to video making, this was necessary for the class, because the students need to understand how music video language evolved throughout the eighties and nineties on to today.

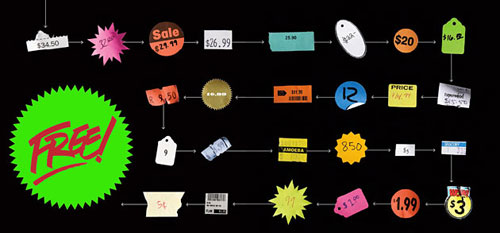

Some of the videos also show early traces of sampling, for example, Trans Europe Express was sampled by Afrika Bambaataa for Planet Rock. Also, the remix of Tour de France juxtaposed with the early version shows how electronic music has evolved while acknowledging the important paradigms set by early electrofunk compositions. The now well known mashups of Christina Aguilera and the Strokes, Madonna and the Sex Pistols, as well as Michael Jackson, Britney Spears the White Stripes and Rick James are some of the most successful remixes in this genre. Part of me admittedly rejects them for their popularity, but the creativity that has gone into the audio remix as well as the video editing have to be noted, because they have at this point set a standard in Remix Culture.

Christina Aguilera and the Strokes, Mashup:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wl85yq_k0V0

Madonna/Sex Pistols Mashup:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ucLIYZ-tyiQ

Madonna Eurithmics Mashup:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dK-

ppQnAl8A&feature=related

Madonna/Depeche Mode:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DW2

YUyeK5FI&feature=related

Michael Jackson/ Britney Spears and Rick James”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6

A8uivUNX0&feature=related

Oasis, “Wonderwall”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FAPtTS0TYtU

Greenday, “Boulevard of Broken Dreams”

http://youtube.com/watch?v=bxfpMGLMZ7Y

Early Version:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=akGR

WdkAxhI&feature=related

Greenday/Oasis with Travis Mashup with Eminem:

http://youtube.com/watch?v=0DzDcAW6GmQ

Yet another twist on the mashup:

http://youtube.com/watch?v=vNLop_nuCzo

Talking Head’s “Burning Down the House”

http://youtube.com/watch?v=st1lH8zcIuQ

&feature=related

Talking Head’s “Wild Wild Life”

http://youtube.com/watch?v=4NXkM8PsPXs

The Cars, “Magic”

http://youtube.com/watch?v=6bEu9wLDjKY

The Cars, “Shake it Up”

http://youtube.com/watch?v=foj81S44_

bE&feature=related

Sex Pistols, “God Save the Queen”

http://youtube.com/watch?v=8z2M_hpoPwk

Ramones, “Rock and Roll High School”

http://youtube.com/watch?v=hLahs7yCprQ

Malcom Mc Claren, “Buffalo Gals”

http://youtube.com/watch?v=7b1zKyVeKgk

Sugar Hill Gang’s Rapper’s Delight:

http://youtube.com/watch?v=diiL9bq

valo&feature=related

In Scrubs:

http://youtube.com/watch?v=

CtAlZB2iqCU&feature=related

Soul Sonic Force’s “Planet Rock”

http://youtube.com/watch?v=9h6pcqC6wrI

Grandmaster Flash’s “The Message”

http://youtube.com/watch?v=k3kRuJhIVIo

Kraftwerk, “Tour De France” Original Version:

http://youtube.com/watch?v=VPowpIR

VOuY&feature=related

Kraftwerk, “Tour De France,” 2003

http://youtube.com/watch?v=sQz-C

ZvkY8k&feature=related

Kraftwerk, “The Robots”

http://youtube.com/watch?v=VXa9tXcMhXQ

Kraftwerk, “Trans Europe Express”

http://youtube.com/watch?v=LWlgbAc3bbM