Remix Defined

For my most in-depth definition of Remix, read “Regressive and Reflexive Mashups in Sampling Culture.” What follows below are excerpts from numerous articles I published since 2006.

Grandmaster Flash

Hacks the DJ mixer. Mid to late seventies

(Image does not necessarily correspond with time period)

Generally speaking, remix culture can be defined as the global activity consisting of the creative and efficient exchange of information made possible by digital technologies that is supported by the practice of cut/copy and paste. The concept of Remix often referenced in popular culture derives from the model of music remixes which were produced around the late 1960s and early 1970s in New York City, an activity with roots in Jamaica’s music.[1] Today, Remix (the activity of taking samples from pre-existing materials to combine them into new forms according to personal taste) has been extended to other areas of culture, including the visual arts; it plays a vital role in mass communication, especially on the Internet.

DJ Kool Herc

Introduces Jamaican Toasting in NYC throughout the seventies

(Image does not necessarily correspond with time period)

The Hip hop DJs improved on the skills previously developed by Jamaican music producers, and Disco DJs during the seventies. They took beatmixing and turned it into beat juggling, which means that they played with beats and sounds on the turntable to create unique momentary compositions. This is known today as turntablism. This practice found its way into the music studio and became part of the tradition of sampling; and sampling is the basis for the popular practice of cut/copy and paste.

Afrika Bambaataa

Plays with the possibilities of sampling, Mid seventies to early eighties

(Image does not necessarily correspond with time period)

The hip-hop DJs play an important part in the cultural shift from a passive consumer model to a consumer/producer model, which is currently in place throughout the Internet, and is most evident in the blogger.

[1] The early form of remix from Jamaica known as “version” is not a remix in the popular sense. Remix (with a capital “R”) is not only defined by material activities but the political contexts of those activities. The remix of NYC was developed in large part due to commercial interests to promote specific songs in a growing consumerist market thriving on the wings of Disco and Hip Hop subcultures. Yet historically, it is agreed that the basic concept of remixing that was defined in NYC was already at play in Jamaica. When considering this, one should keep in mind that the type of consumption that took place in Jamaica’s culture is very different from what took place in popular culture in the United States and othe places of the world, and that this does affect the different names that acts of appropriation attain. In short, there are cultural and political reasons why Jamaican musicians called their remixes “versions” and not “remixes.”

For further information, read the post: History of Dub and “Dub Revolution: The Story of Jamaican Dub Reggae and Its Legacy” by John B

A book to consider: Dick Hebdige, Cut ‘N’ Mix: Culture, Identity and Caribbean Music, (London: Comedia, 1987).

The following section was added as a separate entry on April 26, 2007

The Three Basic Forms of Remix: A Point of Entry, by Eduardo Navas

Image source: Turbulence.org

Layout by Ludmil Trenkov

Duchamp source: Art History Birmington

Levine source: Artnet

(This following text was added to this page to expand my general definition of Remix.)

The following summary is a copy and paste collage (a type of literary remix) of my lectures and preliminary writings since 2006. My definition of Remix was first introduced in my text: Turbulence: Remixes + Bonus Beats (January 2007), commissioned by Turbulence.org. Many of the ideas I entertain in that text were first discussed in various presentations during the Summer of 2006. (See the list of places here plus an earlier version of my definition of Remix). Below, the section titled “remixes” takes parts from the section by the same name in the Turbulence text, and the section titled “remix defined” consists of excerpts of my definitions which were revised for the text Remix: The Bond of Repetition and Representation (January 2009), published in English and Spanish by Telefonica in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

The Three Basic Forms of Remix were revised, yet again, for the text Regressive and Reflexive Mashups in Sampling Culture, which was published originally on Vague Terrain in June 2007, and eventually revised once more to be published on the book Mashup Cultures in 2010, edited by Stefan Sonvilla-Weiss. It is in the last revision where I introduce the concept of the Regenerative Remix, which I define below after the three basic remixes.

———–

REMIX DEFINED

To understand Remix as a cultural phenomenon, we must first define it in music. A music remix, in general, is a reinterpretation of a pre-existing song, meaning that the “aura” of the original will be dominant in the remixed version. Of course some of the most challenging remixes can question this generalization. But based on its history, it can be stated that there are three types of basic remixes, which extend in culture as a fourth type, which I refer to as Regenerative. The first remix is extended, that is a longer version of the original song containing long instrumental sections making it more mixable for the club DJ. The first known disco song to be extended to ten minutes is “Ten Percent,” by Double Exposure, remixed by Walter Gibbons in 1976.[1]

Image source: Vinyl Masterpiece

The second remix is selective; it consists of adding or subtracting material from the original song. This is the type of remix which made DJs popular producers in the music mainstream. One of the most successful selective remixes is Eric B. & Rakim’s “Paid in Full,” remixed by Coldcut in 1987. [2] In this case Coldcut produced two remixes, the most popular version not only extended the original recording, following the tradition of the club mix (like Gibbons), but it also contained new sections as well as new sounds, while others were subtracted, always keeping the “essence” of the song intact.

Image source: Rate Your Music

The third remix is reflexive; it allegorizes and extends the aesthetic of sampling, where the remixed version challenges the aura of the original and claims autonomy even when it carries the name of the original; material is added or deleted, but the original tracks are largely left intact to be recognizable. An example of this is Mad Professor’s famous dub/trip hop album No Protection, which is a remix of Massive Attack’s Protection. In this case both albums, the original and the remixed versions, are considered works on their own, yet the remixed version is completely dependent on Massive’s original production for validation.[3] The fact that both albums were released at the same time in 1994 further complicates Mad Professor’s allegory. This complexity lies in the fact that Mad Professor’s production is part of the tradition of Jamaican dub, where the term “version” was often used to refer to “remixes” which due to their extensive manipulation in the studio pushed for autonomy.[4]

Image source: Last FM

Allegory is often deconstructed in more advanced remixes following this third form, and quickly moves to be a reflexive exercise that at times leads to a “remix” in which the only thing that is recognizable from the original is the title. But, to be clear, in terms of music, no matter what, the remix will always rely on the authority of the original song. When this activity is extended to culture at large, the remix is in the end a rearrangement of something already recognizable; it functions at a second level: a meta-level. This implies that the originality of the remix is non-existent, therefore it must acknowledge its source of validation self-reflexively. In brief, the remix when extended as a cultural practice is a second mix of something pre-existent; the material that is mixed at least for a second time must be recognized otherwise it could be misunderstood as something new, and it would become plagiarism. Without a history, the remix cannot be Remix.[5] This does not imply that a person needs to know that something is a “remix,” however, but that this is a pre-requisite for our culture to function–whether it is transparently acknowledged by the remixer or not.

The extended, selective and reflexive remixes can quickly crossover and blur their own definitions. Based on a materialist historical analysis, it can be noted that DJs became invested in remixes which inherited a rich practice of appropriation that had been at play in culture at large for many decades. Below are brief definitions with visual examples.

REMIXES

Extended Remixes

The Extended Remix was an early form of remix in which DJs from New York City became invested. On close examination this was a reaction against the status quo, where everything was made as brief as possible, from radio songs to novels. I argue that due to this, the extended remix is not found in mass culture prior to this period.

The Disco DJs, going against the grain, actually extended music compositions to make them more danceable. They took 3 to 4 minute compositions that would be friendly to radio play, and extended them as long as 10 minutes.[6] In the seventies this was quite radical because in fact, it is the summary of long material that is constantly privileged in the mainstream–which is true even today. The reason behind this tendency has to do in part with the efficiency that popular culture demands. That is, everything is optimized to be quickly delivered and consumed by as many people as possible. An obvious example of this tendency from history is the popularity of publications like Reader’s Digest, which offers condensed versions of books as well as stories for people who want to be informed but do not have the time to read the original material, which is often more extensive. [7]

Image source: E Bay

Another recent activity that is now emerging on the web is the two-minute replay available for TV shows like “Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip.”8] If you missed the show when it aired, you can spend just two minutes online catching up on the plot; in essence, this is a more efficient version of Readerâ’s Digest for TV delivered to your Internet doorstep. This two-minute replay is also called “video highlights. At the same time, this optimization of information allows entire programs to be uploaded by average consumers in short segments to community websites like Youtube, which in the end function as promotion for TV media.[9] But YouTube falls within the paradigm of the Regenerative Remix, as I explain below.

Image source: Youtube

Selective Remixes

For the Selective Remix the DJ takes and adds parts to the original composition, while leaving its spectacular aura intact. An example from art history in which key codes of the Selective Remix are at play is Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917); [10] this work consists of an untouched urinal (save for a traditional artist signature) to reinforce the question, what is art? And codes of a second level remix on Duchamp can be found in Fountain (after Marcel Duchamp) by Sherrie Levine who, in 1991, questioned Duchamp as a privileged male artist and his urinal as art, leaving intact Duchamp’s aura as an artist but not the Urinal’s spectacular aura as a mass produced object. [11] In both of these cases there is subtraction and addition (selectively–hence the term, Selective Remixes).

Image source: Turbulence.org

Layout by Ludmil Trenkov

Duchamp source: Art History Birmington

Levine source: Artnet

A second example where key codes of the Selective Remix are at play can be found in DJ culture itself. Notice how the CD remixer gains authority by allegorizing the turntable. In this case the Technics 1210 functions similarly to Duchamp’s urinal: the basic turntable designed for listening was appropriated by the DJ to mix and scratch music live; it was used as an actual musical instrument, and Duchamp appropriated a urinal to recontextualize it as art. It is crucial to note that the necessity for precision in performance by turntablists led to developing a specialized turntable that could withstand physical abuse, while for Duchamp, it was enough to leave the urinal intact, save for the artist’s signature (R. Mutt). Then the Technics SL-DZ 1200 similarly to Levine’s urinal, selectively allegorizes and appropriates elements from the Technics 1210 turntable; in this instance the critical elements that validate the turntable in DJ Culture are not only left intact, but in fact celebrated.

Images source: Panasonic Europe

Reflexive Remixes

The Reflexive Remix differs in various ways from the Selective Remix; it directly allegorizes and extends the aesthetic of sampling as practiced in the music studio by seventies DJs, where the remixed version challenges the aura of the original and claims autonomy even when it carries the original’s name. In culture at large, the Reflexive Remix takes parts from different sources and mixes them aiming for autonomy. The spectacular aura of the original(s), whether fully recognizable or not must remain a vital part if the remix is to find cultural acceptance. This strategy demands that the viewer reflect on the meaning of the work and its sources-even when knowing the origin may not be possible.

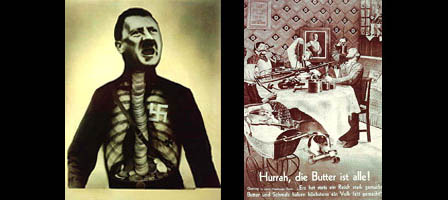

An example from art history in which the codes of the Reflexive Remix are at play is the work of John Heartfield, who takes material out of context to create social commentary. His Photo-montages like Adolf the Superman: Swallows Gold and Spouts Junk[12] and Hurrah, the Butter is All Gone,[13] question the very subject that gives them the power to comment. In the former, Hitler, as the title connotes, is presented swallowing gold and is questioned as a leader of Germany; while in the latter, a German family is having dinner, eating military weapons, thus the stability of the home is questioned due to German politics. In his case, the spectacular aura of the source image (like in the second remix) is left intact-but only to be questioned along with everything else: we believe the image but question it at the same time due to the dual transparency of a montage and the realism expected of a photo-image; the work then gains access to social commentary based on the combination of recognizable images.

Image source: Turbulence.org

Layout by Ludmil Trenkov

Sources: towson.edu

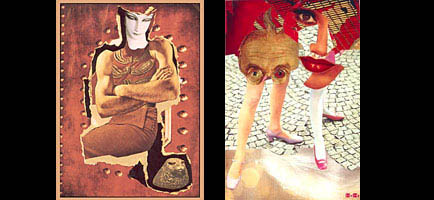

Another example from art history where the codes of the reflexive remix can be found is the work of Hannah Hoch. Her collages blur the origin of the images she appropriates; the result is open-ended propositions. Her work often questions notions of identity and gender roles. Yet, even when it is not clear where the material comes from, her work is still fully dependent on an allegorical recognition of such forms in culture at large in order to attain meaning. This is the case in pieces like Grotesque [14] and Tamar. [15] Although they were made 30 years apart, both decontextualze the objects they appropriate. Here we have body parts of men and women remixed to create a collage of de-gendered figures. The authority of the image lies in the acknowledgment of each fragment individually, and a specific social commentary like the one found in Heartfield’s work is no longer at play; instead, each individual fragment in Hoch’s work needs to hold on to its cultural code in order to create meaning, although with a much more open-ended position.

Image source: Turbulence.org

Layout by Ludmil Trenkov

Tamar source (left): yellowbellywebdesign

Grotesque source (right): Adam Art Gallery

For Heartfield and Hoch the subject which gives the work of art its authority is actually questioned; the result is a friction, a tension that demands that the viewers reconsider everything in front of them. This is what makes their art powerful.

Regenerative Remixes

The Regenerative Remix consists of juxtaposing two or more elements that are constantly updated, meaning that they are designed to change according to data flow. I choose the term “regenerative” because it alludes to constant change, and is a synonym of the term “culture.” Regenerative while often linked to biological processes is extended here to cultural flows that can move as discourse from medium to medium, although at the moment it is in software that it is best exposed. [excerpt from Regressive and Reflexive…]

Principles of the Regenerative Remix in culture at large are at play in Wikipedia. The entries to the online encyclopedia are constantly revised and updated by different contributors; when a controversial entry is made, a discussion ensues and a posting is placed at the top of the site explaining the current state of debate. Wikipedia, then, is dependent on constant-updating, which is essential for the Regenerative Remix.

Image source: Wikipedia.org

Another example is Youtube, a site, which like Wikipedia is driven by the community. If a video is offensive or deemed inappropriate, the community will let YouTube staff know immediately. Youtube also has a complex tie in with the corporate media, in which copyright infringement is always present, and it is quite common that when a corporation finds it to their benefit, they demand their material to be removed if it was posted without permission. This opens the door to the complexities brought about by the creative possibilities of “free culture” and “remix culture.”

For a detailed analysis of how the Selective and Extended Remixes are at play in new media art, please read the section “Remixes” in Turbulence: Remixes + Bonus Beats. For an in-depth analysis of the Regenerative Remix, please read Regressive and Reflexive Mashups in Sampling Culture.

There are many other examples from art history and popular culture which can be presented. Neo-dada material by Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns and their contemporaries can be connected with the reflexive remix, while work by Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein can be related to the Selective Remix. The Extended Remix, however remains unusual, except in the club remixes and art projects. The reasons for this will eventually be released in a more exhaustive publication.

In conclusion, what is crucial is to understand how different acts of appropriation throughout history, such as the ones revisited above, enable people to entertain Remix as part of the consumer/producer model often refer as the “prosumer” currently at play in culture.

[1] Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton, Last Night a DJ save my Life (New York: Grover Press, 2000) , 178-79.

[2] Paid in full was actually a B side release meant to complement “Move the Crowd.” Eric B. & Rakim, “Paid in Full,” Re-mix engineer: Derek B., Produced by Eric B. & Rakim, Island Records, 1987.

[3] Ulf Poschardt, DJ Culture (London: Quartet Books, 1995), 297.

[4] Dick Hebdige, Cut ‘n’ Mix: Culture, Identity and Caribbean Music, (London: Comedia, 1987), 12-16.

[5] DJ producers who sampled during the eighties found themselves having to acknowledge History by complying with the law; see the landmark law-suit against Biz Markie in Brewster, 246.

[6] Brewster, 178-79.

[7] Reader’s Digest, http://readersdigest.com (October, 2006).

[8] “Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip,” http://nbc.com, September 2006,

[9] The 2007 Grammys can be seen in pieces almost in its entirety. See “Grammys 2007,” Youtube.org 2007 (April 15, 2007), http://youtube.com/results?search_query=grammys+2007&search=Search.

[10] For an online reproduction of the famous Richard Stieglitz photograph visit: “Fountain” Art History Birmington,http://arthist.binghamton.edu/duchamp/fountain.html , (November 2006).

[11] For an online reproduction of Levine’s appropriation visit “Sherrie Levine,” Artnet, http://www.artnet.com/magazine/features/cfinch/finch5-7-4.asp, (October, 2006).

[12] For an image of Heartfield’s “Superman,” see: Towson.edu, http://www.towson.edu/heartfield/images/Adolf_the_Superman.jpg, (October, 2006).

[13] For an image of Heartfield’s “Butter’s all Gone,” see http://www.towson.edu/heartfield/images/Hurrah_the_Butter_is_all_gone.jpg, (October, 2006).

[14] For an image of Grotesque visit Adam Art Gallery http://www.vuw.ac.nz/adamartgal/exhibitions/2002/big/lightsandshadows-Höch-lg.html, (October, 2006).

[15] For an image of Tamar ,visit “Hannah Hoch’s “Dompteuse(Tamar)”, http://www.yellowbellywebdesign.com/Höch/dompu.html, (October, 2006).