Notes on “Everything is a Remix: The Force Awakens”

Everything is a Remix: The Force Awakens from Kirby Ferguson on Vimeo.

Kirby Ferguson has released a fifth episode of Everything is a Remix, this time focusing on the work of J.J. Abrams, particularly his latest film Star Wars: The Force Awakens. In this occasion Ferguson goes into some detail of how different types of remixes are developed. He presents two key points that allow him to explain how Abrams’s remix approach is different from George Lucas’s. While doing this he also poses a question that appears to be inevitable once culture becomes aware of how the creative process has always functioned in terms of borrowing, citing, appropriating, and recycling material: is remix reaching its limits?

The first premise that Ferguson introduces is the concept of copying major story elements as opposed to directly copying scenes or shots. He explains that the former is what Abrams currently does, and the latter is what Lucas did. This approach is what I have defined in various publications as cultural citation. [1] (For a specific explanation of how cultural citation functions see my previous notes on Ferguson’s first three episodes). Both Lucas and Abrams actually perform two different forms of cultural citation. Lucas developed his shots by close emulation, which is what bands such as Led Zeppelin did when they took blues compositions to develop their own songs , or what Quentin Tarantino continues to do in his films (See my first notes). Copying entire plot lines fall under the broad practice in literature usually discussed under the term of intertextuality, which is the ability to embed ideas within ideas to develop new works. This particular form of “borrowing” or appropriating is difficult to track because it is more about being aware of references held in one’s memory–in other words, one must know the history prior to viewing the work in order to notice the resemblances that would go unnoticed for a person who is marginally familiar with the subject. But with the increase of material being produced even in this broad manner and our ability to track all types of recyclability with quantification of data, this more broad form of immaterial borrowing is becoming more obvious to people who normally would not worry about such details in the creative process.

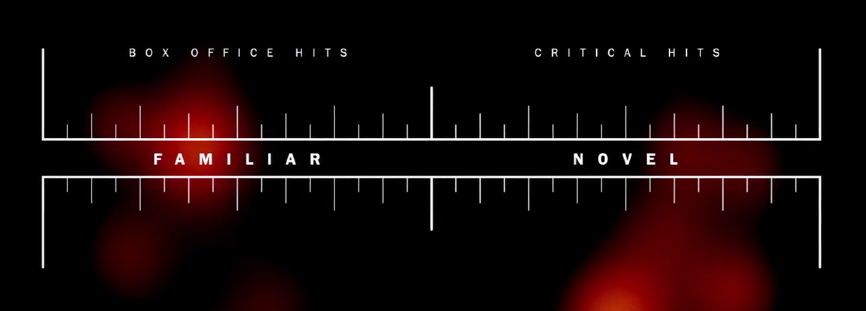

The other premise that Ferguson presents is how remix functions in large part with what he refers to as “familiar.” He actually contrasts this term with the “novel” to develop a diagram of his own that shows that the most successful remixes (if we are thinking in commercial terms primarily, according to his conclusion in this episode) are the ones that fall right at the middle of both the familiar and the novel.

Figure 1: image capture from Ferguson’s “Everything is a Remix: The Force Awakens,” at minute 6:56.

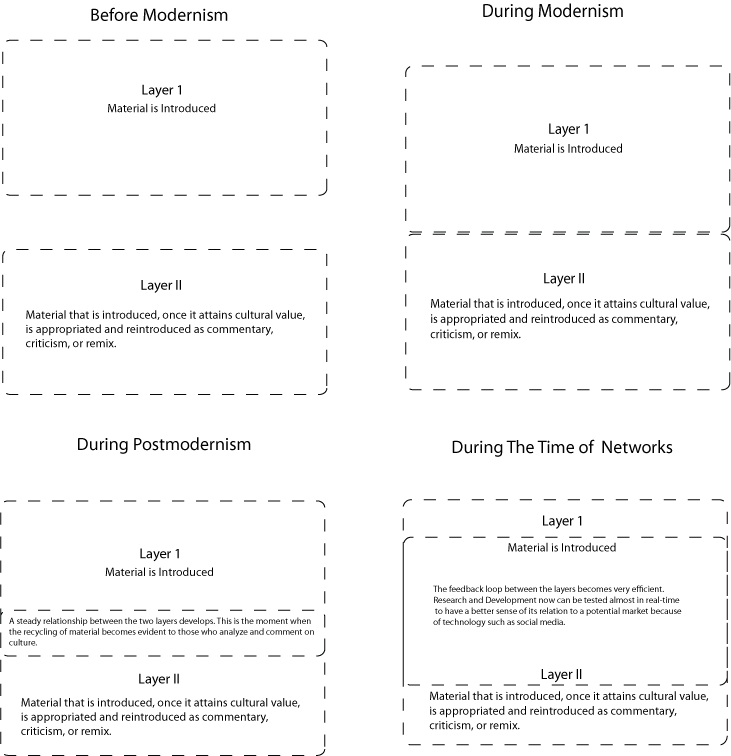

The familiar and the novel resemble my own definition of the framework of culture, in which I explain that there are two layers. The first layer is where something is introduced (Ferguson calls this “novel”) and the second layer is where that which is introduced attains cultural value and is then ripe for remixing (Ferguson calls this “familiar.”) The diagram towards the end of his episode (see figure 1 above) visualizes in different fashion what I presented in past articles with various diagrams of the framework of culture (See figure 2 below).

Figure 2: For an explanation of these diagrams see “The Framework of Culture” and “Culture and Remix: A Theory of Cultural Sublation”[2]

This comparison of terms in a way appears to be a remix of remixes in itself since Ferguson and I may well be part of “multiple discovery” a process he explains at the end of his third episode in the series. It leads us back to the question on whether or not remixing is reaching its limits. Ferguson argues that remix can be successful when it is used in a balanced approach when it takes enough of the familiar and enough of the novel in order to present a work that is entertaining to the audience. The question that remains with Ferguson’s proposition is if the novel and the familiar as he presents them are reconfigured to become a type of formula to develop remixes that will be more likely successful? (According to how he defines success.) Can this be possible one may ask, when it is well known that the “novel” is that which resists to become part of the mainstream (or using his term “familiar”), even when parts of it may clearly be incorporated? This question is likely to remain unanswered as it has proven to be part of the drive for creativity by those who remain on the margins and decide to develop a vision of their own. Such individuals are at the periphery, and to be there, the price to question a more balanced approach (between the familiar and the novel) appears inevitable. This may well be a residue of the well known debates of high and low culture beginning in late modernism well into postmodernism.

In terms of at least popular success, it appears that Ferguson’s very own series may be a good example of balancing the familiar with the novel, as he has become an influential figure in popularizing the importance in understanding how remix (as a “novel” creative form) functions well when it is balanced as he explains in his fifth episode. More importantly his short films help make a case to understand why it is crucial that we not only become aware of the creative process, but also that we practice cultural production in fair fashion. On this last point Ferguson appears to give general references to the sources that have influenced him whenever he can, although one may wonder if some of his references go unacknowledged and credit is not attributed to those people from whom he has borrowed to develop his arguments? Slippage of accreditation on his part may be unavoidable given that his documentaries in the end are quite general and borrow from literally hundreds of people who have contributed to the main premises he taps into. This question is more than crucial among individuals doing in-depth research.

Also, the reality is that cultural production appears to be moving towards the speed of speech (we are producing media at the moment based on how fast we may type and may surpass this very soon to the speed of thought years from now). It is becoming more and more difficult to keep track of all things we would need to cite in order to be fair to those who have performed important research that informs our opinions and points of view. [3] But doing this remains important because on one level, one may not recognize a remix if the citation is not recognizable (this may not be so important if one is not interested in making sure people know that what one is producing is a remix). In terms of developing new arguments, it is a matter of ethical etiquette for one can always claim that one reached certain conclusions based on independent research, and this is where the community is important. Perhaps the most basic automated peer reviewer may be Google, who can show us who has written what fairly well. So, loss aversion (another term by Ferguson) may become reconfigured, perhaps even acceptable, or strategically displaced, in the future and the ethics behind such omissions may change as the concept of the writer as author shifts into new forms.

The downside of Ferguson’s series as much as I like it, and I particularly like “Everything is a Remix: The Force Awakens,” is that all episodes may well be shooting for the middle of the road towards that balance that Ferguson considers “explosive.” The challenge for future episodes in the series is whether or not they will become too formulaic, a bit like the Star Wars films are likely to become a successful template for money making, now that Disney owns the franchise. The challenge for remix as a practice in the end is to remain pushing itself by reinventing new forms and ideas with what is already invented–in order to make the remix truly different and new; and if it is done really well, such work could be novel, functioning at the edges of the first layer of the framework of culture. If remix stops doing this, it may well reach its limit, but something else will likely evolve out of such possible exhaustion–and that will be the difference of remix according to its very own repetition.[4]

[1] I began discussing the principles of this term in 2009. The basic definitions were published in 2012 in my book Remix Theory: The Aesthetics Sampling. A more developed version can be found in my article “Culture and Remix: A Theory of Cultural Sublation (2014).” Earlier versions of this can be found in “The Framework of Culture: Remix in Music, Art, and Literature (2013),” and “The New Aesthetic and the Framework of Culture (2012).”

[2] There is a fifth diagram that shows how meta-loops are at play in our current state of production. See “Culture and Remix: A Theory of Cultural Sublation” (2014)

[3] I go over the implications of the ever-increasing speed of production in “Regenerative Culture,” (2016).

[4] For the relation of difference, repetition and remix see David J. Gunkel’s Book, Of Remixology (2015).