Text and Interview for the Exhibition “An 8-bit Moment in Gameplay,” by Eduardo Navas

Image and text source: gallery@calit2

The following text and interview were written for the exhibition “An 8-bit Moment in Gameplay: [giantJoystick],” featuring a ten-foot scale working model of the Atari Joystick by artist and media theorist, Mary Flanagan. The exhibition takes place from February 4 to March 17, 2008. You can read more about it at http://gallery.calit2.net.

Both, text and interview, focus in part on the concept of gameplay and its relation to the mainstream as well as the fine arts. The texts are worth archiving in Remix Theory because they shed light on video game culture which, as it’s no secret, relies extensively in concepts of appropriation intimately linked to the current practice of remixing (Remix). For instance, video game players, or gamers, are no longer only expected to play games as out of a package, or as released online; gamers are expected to actually contribute to the game infrastructure by customizing it, either for personal play, or for the enjoyment of the larger community, following the tradition of open source. Examples of this activity are numerous (see Wikipedia list).

Video game culture is in large part fueled by the same principles that have made networked culture possible: the possibility to share and remix code as desired, to then re-release it for the community to use and improve upon, again. This tendency follows my proposition about the blogger which encapsulates a consumer/producer model that is proactive in media culture. Some skepticism is healthy here, and it must be acknowledged that romanticizing such model is a real danger for new media and remix culture.

The following texts, then, offer a window to some of the issues that inform gameplay today. The texts can be considered valuable because they reflect upon and extend the opinion of one of today’s gameplay insiders, Mary Flanagan.

TEXT: An 8-bit Moment in Gameplay: [giantJoystick]

gallery@calit2

Atkinson Hall

University of California, San Diego

February 4 to March 17, 2008

Featuring [giantJoystick] by Mary Flanigan

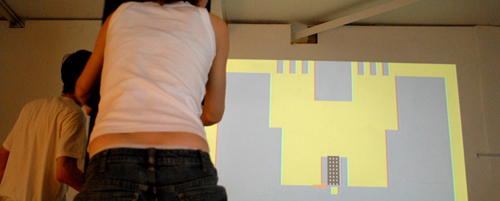

gallery@calit2 proudly presents “An 8-bit Moment in Gameplay: [giantJoystick],†featuring a working, large-scale game-interface-sculpture designed for collaborative play by artist and media theorist Mary Flanagan. [giantJoystick] (2006) takes us back to the early days of video games when they entered the home. It features classic Atari games from the 1980s, including Adventure, Asteroids, Breakout, Centipede, Circus Atari, Gravitar, Missile Command, Pong, Volleyball, and Yar’s Revenge. The recontextualization of such classics opens a space to reflect on the brief and dense history of video games and the aesthetics of play.

Video game consoles, which offered low-resolution graphics known as 8-bit, were made popular in large part by Atari in 1977. However, video games did not enter the average household in full force until the early 1980s. To many, the years 1979 to 1986 are remembered as the “golden age†of video games – a period when popular culture would also be exposed to digital technology with the introduction of the personal computer. It is, then, not surprising that video games entered the home in this time period. Flanagan’s [giantJoystick] takes us back to this pivotal moment by turning the Atari joystick into a work of art, which carefully combines her interests in art-making as well as gameplay.

Flanagan considers [giantJoystick] as a form of social sculpture. The term is used by Joseph Beuys to extend the aesthetics and critical practice of art not only to artists, but to anyone interested in questioning culture. Beuys reflected upon the possibilities of art production by drawing, performing, and creating sculptures that defied the understanding of art practice in the decades after World War II. Flanagan, in turn, uses the term social sculpture to allude to the possibilities of real social change when individuals involved in gameplay become aware of the possibilities for critical expression and reflection in the discourse of video game culture. Her strategy is also closely linked to the tradition of pop art; clear references can be made to Claes Oldenburg’s oversize sculptures such as Spoon and Cherry (1985-88) or Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes (1969). The end result is an installation that combines art and video game aesthetics, opening the door for multiple readings.

[giantJoystick], for instance, can be read as a feminist commentary on video game culture, especially when considering that historically video games have been defined by young boys. It can also be read as a critical reflection on the work of art. Traditionally, gallery visitors are not allowed to touch art. With [giantJoystick], however, viewers are not only asked to interact with the work, but also to get extremely physical to the point of breaking a sweat, all while collaborating in gameplay with others. Most importantly, visitors are expected to have fun, something usually kept at bay when entertaining serious art.

Mary Flanagan’s [giantJoystick] ultimately creates a rhetorical space that bridges what is known in game culture as the magic circle (a space defined by rules of play) with the aesthetics of the white cube (the rules of engagement of the art gallery), reinvigorating the recurring tendency in art practice to look to culture at large for inspiration.

Mary Flanagan Interview:

Social Change, Video Games and the Visual Arts

by Eduardo Navas

Mary Flanagan is an artist and media theorist invested in developing games for social change and performance/action installations. Based on her interests Flanagan produced [giantJoystick] in 2006, and gallery@calit2 is proud to present this working large-scale game-interface from February 4 to March 17 of 2008. As it has been outlined above, [giantJoystick] brings together Flanagan’s diverse interests as a cultural producer. The oversize custom-made playstation is evidence that Flanagan’s production borrows not only from the visual arts and video games culture, but also popular culture. [giantJoystick] is the result of a new form of critical practice which does not fit neatly into previous models. For this reason, gallery@calit2 is excited to present the following interview with Mary Flanagan in which she shares her experiences as a young girl who played video games, and as an artist invested in social change. The following interview is an important source for the above text. gallery@calit2 publishes it with the aim to shed light on the creative process of the artist.

Eduardo Navas: You use the term Social Sculpture to describe [giantJoystick]. Could you elaborate how you see your work in relation to Joseph Beuys’ aesthetic and political views?

Mary Flanagan: I use the term Social Sculpture to suggest the alignment of [giantJoystick] (which we will refer to as [gJ] from here on) not only to my other projects (particularly my social activist research lab) but also to the larger idea of creativity being applied to all human endeavors. Play, to me, can be instrumental in realizing some of the goals of both Beuys and Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925), whose Anthroposophical Society advocated holistic medicine and even organic farming in addition to pursuing social ideas in human freedom, democracy, and sustainable economic forms. I use the concept of social sculpture to consider how an object or artifact can work to structure, on the small scale, interesting and progressive social interaction, and on the large scale, contribute to the reshaping of larger social and political organizations– literally shaping and molding the world we live in. Beuys’ project was ultimately very political, and so is mine.

In contemporary US culture, there is little dialogue about serious issues: class differences between rich and poor are the highest since the troubled Gilded Age of the 1920s, with increased, dire ecological consequences. Corporate culture has continued to conquer global production, consumption, and consciousness, disempowering citizens, and unhinging much of the social fabric and traditional means of living. Then we have corporate driven violence and war.

The response to make a play object in the fact of such a grim framework may appear frivolous. But note that games are popular right now for a reason — they present fun, but of course, escapist scenarios in which we are faced with quantifiable enemies and concrete goals. We might be onto something if we can use this model for real social change. And, if people are meeting physically with this joystick, breaking down communication barriers and playing together, this may be the start of an interactive dialog which might be transformative, even healing.

EN: Based on your answer you do see [gJ], contributing in some way to a model of real social change; would you then consider your critical investment linked to activism? I think of the great interest in the work of Guy Debord and other Situationists, which now is being revisited to talk about play as a form of critical intervention in the real world. Do you see [gJ] or other projects you have developed contributing to this dialogue?

MF: I do see many of my play-related projects linked to political and social activism. That said, I don’t think just because something is playful it is automatically subversive or progressive. Not everyone has the same permission to play. For example, a group of primarily white college students playing a mobile media game in a cemetery or on the streets of New York would be read very differently than, say, a group of non-English speaking Latino players or young African Americans congregating en masse to play a game. So this must pervade a designers consciousness: how can we expand the permission set of who is allowed to play? This is also the same cautionary approach I have with the current revival in Situationist thinking… who is allowed to drift? Under what conditions would it be possible to propose larger, universal play paradigms? What would have to change?

And of course these questions lead to one doing design work that calls into question and reformulates, for example, the role of technologist (who is the maker, and how can more people be in this position?), and the role of spectator (who is the artist, and how can more people be in this position?).

EN: How do you contextualize [gJ] in your critical interest of play and locative media? Are there any links, or do you see it as a completely separate research endeavor?

MF: I have multiple tracks in my research project, and this work and locative media have in common my interest in participatory culture. [gJ] does not claim to represent the space in which it is housed, and is a rather obvious intervention, so its quite the opposite of most locative media projects. This work falls more in line with inquiries into collaborative play and alternate reward systems in game design research. Sometimes, my research erupts as artwork; at other times, it finds its home in collaboratively produced research projects at my laboratory.

EN: [gJ] can be read as a subversive work of art. By this I mean that it puts in question some general assumptions about sculpture. For instance, it demands to be not only touched but also played; it’s designed to withstand heavy physical abuse. Do you see [gianJoystick] in line with the work of Felix Gonzalez Torres, for example, who often created, shall we say, interactive artworks that demanded certain actions and destruction of the work from the viewer? I think of his candy installation “Untitled, Public Opinion,” (1991) which was completed when the museum visitor took away a piece of candy. Or other artists from his generation, who were definitely influenced by conceptual art, but were also heavily invested in making objects that somehow questioned themselves.

MF: Both my work and the work of Gonzalez Torres move the attention from the object to the object’s relationship. As Nicholas Bourriaud wrote, “the aura of artworks has shifted to their public” (Relational Aesthetics (1998) 2002, 58). This also is, for me, informed by software art and the lack of “true object” so highly prevalent in art history. Dialog with software art, however, stops at the form: the form of the joystick itself functions as a fetish or totem as well, constantly referring to game culture.

[gJ] formulates an interaction by posing questions about play, touch, embodiment. It does so primarily through its scale: after all, if the work were smaller, one player can play on his or her own, and the sense of participatory play and collaboration would be lost.

EN: The fact that [gJ] demands that gallery visitors become heavily invested in the work with their bodies and actually sweat after playing for a few minutes may open a door for critics skeptical of New Media and art games to claim that the usual critical distance necessary for a work of art to be reflexive about its context may be lost. How do you respond to such criticism, which in part has separated New Media art from the work of art usually found in more commercial art galleries?

MF: I think the disquiet that commercial art galleries display towards new media art is not about critical distance but about the financial conservativism they carry forward (or imagine) from their audience, collectors. We are in a cycle of quite conservative investment practices in the arts. In addition, many new media artists have not wished to sell their work in more traditional ways, because it may be against the ideas the work is investigating.

EN: [giantJoystick] is a phallus. It should be safe to say that many gallery visitors give it such reading, yes? If so, how do you see your work in line with feminism: the fact that you, a woman, has created a sculpture, which you also explain could be seen as nostalgic, making reference to a gaming past ruled by mainly boys? You also explained in one of your videos that you were the only kid in your neighborhood who played video games, how does this relate to the stereotypes that have defined video games?

MF: I’ve discovered at openings and public events that many visitors new to the work initially assume that it is created by a male artist! Which is very fun for me, because I have been significantly involved with feminist art–this poses a challenge that involves gender assumptions in popular gaming culture, and in art practice as well. [gJ] is definitely nostalgic for a significant number of players/viewers, and this can be useful of course, because ultimately, nostalgia may end up being a great tool if used for particular ends… The fact is, male gaming culture is appropriated through this work for play, yes, but also for a kind of reconfiguration of who can play and how we play.

I had a rather lengthy, extended childhood where I played and read far longer than most children I encountered, male or female. This involved computer play, but also dollplay and building fantasy structures. I also busied myself with Rube Goldberg style contraptions, telepathy, elaborate costumes, etc.

EN: You consider [gJ] to be in a “public space.” But how public is this space really? Is the art gallery really a public space? Do you see your gaming installation opening the door to a new type of audience, perhaps? If so what kind?

MF: This work has not only functioned within a gallery space. It was in residence at the London Games Festival and seems to go to venues with a lot of unusual ‘gallery’ traffic, such as the Beall Center and Laboral in Spain. Ideally, it would be housed in a space where a wide range of players and viewers could encounter the work. The initial plan was for a public artwork, linking several joysticks in various global cities, so collaborations could take place between a group in, say, Berlin, and a group in Taipei. This is still on the burner.

That said, this work does attract groups to art spaces that might not normally visit them. This too is a wonderful opportunity to bridge those interested in the art scene with, well, everyone else. By the way, I didn’t enter a formal Western art gallery or museum until I was of college age. So, I’m interested in those kinds of radical transformations we can imagine which cross cultural, economic, and linguistic barriers.

EN: [gJ] is definitely about the aesthetics of video games. But how do you see your intervention of the Atari 2600 when considering the concept of play, or gameplay? The often cited “magic circle” comes to mind. How do you see [giantJoystick] relating to the concept of the magic circle and playing by the rules? Are there any similarities between the rules of play that make the magic circle special, and the gallery space?

MF: Huizinga be praised! The sheer absurd scale of [gJ] creates a kind of magic circle all on its own, whether it is set within a gallery or not. Actually, I would say the gallery atmosphere tends to have its own, competing magic circle, where, as you have noted in your questions, the rules are “don’t touch,” or “behave quietly.” Involving the body is a risky proposition, reminiscent of happenings and other participatory events. By using games that many people might be familiar with (or that are simple enough to parse on one’s own due to common game conventins), participants seem more willing to take on play in this embodied way. Sometimes groups get to shouting and yelling as well.

gallery@calit2 would like to thank Center for Research and Computing in the Arts (CRCA) for their support in the realization of this exhibition.

Lascia un commento

You must be logged in to post a comment.