Che: Recontextualization of an [a]historical Figure, by Eduardo Navas

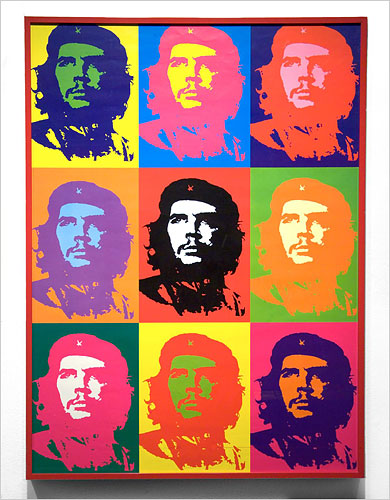

“The Warhol Che,” artist and year unknown, an example of the image’s ubiquity.

Image source: NYTimes

Che Guevara got some attention at the beginning of 2009 with Steven Soderberg’s film Che, starring Benicio del Toro. More recently, Che is the subject of a book titled, Che’s Afterlife, by Michael Casey. The book is reviewed by the New York Times as a detailed account of Che’s famous image taken by Alberto Díaz Gutiérrez, known professionally as Korda. The story goes that Korda took the photograph during a funeral in Cuba. Korda’s creativity was not only in knowing when to take the photograph, which is for what most photographers are praised, but also in knowing how to crop it. To quote directly from the New York Times:

“By radically cropping the shot, snipping out a palm tree and the profile of another man, Korda gave the portrait an ageless quality, divorced from the specifics of time and place.”

This divorce is what Walter Benjamin noted in the first half of the twenty century in his well-known essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” An essay that many cultural critics have cited and will probably cite, because Benjamin foresaw many of the elements that today inform media culture in all areas of reproduction.

Benjamin’s understanding of the possibility of decontextualization through reproducibility is today in many ways well understood in popular culture; taking something out of its original culture with the potential of infinite appropriation by others for diverse purposes is almost a natural act to the average consumer. In fact, this is what Casey’s book is about: how Che’s image was decontextualized from its original place to become a vessel for diverse agendas. Since he died, Che has been, both, idealized and demonized by people with opposing political points of view. His image has also been used on countless T-shirts and every imaginable accessory, including Bikinis worn by super models, as the Times notes.

Korda’s cropping exposes the power of selectivity as a creative act, which made Che a universal figure around the world. The universal figure is often the subject of critique for academics, who, due to their preoccupation with the loss of history, tend to focus on specifics. This is understandable because when a subject is decontextualized and abstracted to become just another vessel for reproduction, it can be manipulated to mean anything. This is what happened to Che’s image.

Casey’s book actually is about recontextualizing Che’s photograph: he examines the image’s complex and never ending history in popular culture. But by tracing the many reproductions, what Casey is paradoxically doing is also contributing to the image’s ahistoricity, meaning its ability to gain popular recognition without the necessity for viewers to understand its original context, and actual history. In other words, Che is rehistoricized in Casey’s book, but this process in itself is possible because of popular culture’s ahistorical interest in Che as an universal figure. This conundrum is what makes iconic figures increasingly popular: the Historical and ahistorical are promoted by the same act of recontextualization.