SPECFLIC 2.6: An Interview with Adriene Jenik, by Eduardo Navas

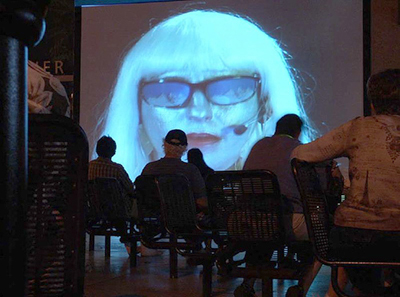

Adriene Jenik lecturing at Calit2

Images and text source: gallery@calit2

Note: The following is an interview published for the exhibition SPECFLIC 2.6 and Particles of Interest: Installations by Adriene Jenik and *particle group* on view from August 6 to October 3, 2008 at gallery@calit2. In this Interview Jenik shares the creative process behind her ongoing multi-faceted installation SPECFLIC, which points to a future where books have become rare objects.

Adriene Jenik combines literature, cinema and performance to create works under the umbrella of Distributed Social Cinema. For Jenik, this term means that the language of cinema has been moving outside of the conventional movie screens on to different media devices, which today include, the portable computer, GPS locators, as well as cellphones. Earlier in her career, Jenik worked with video and performance, and eventually she produced CD-Roms, such as “Mauve Desert: A CD-ROM Translation” (1992-1997). Jenik’s practice took a particular shift towards network culture when the Internet became a space in which she could bring together her interests in film, literature, and performance. “Desktop Theater: Internet Street Theater” (1997-2002) was a virtual performance which took place in an online space. It was based on Samuel Becket’s play Waiting for Godot. In line with these works, SPECFLIC 2.6 is the result of Jenik’s interest in the relation of networked culture to film, literature and performance. The installation, then, is also another shift in Jenik’s interest in the expanded field of storytelling. In the following interview, Jenik shares the influences and aesthetical concerns that inform SPECFLIC 2.6

[Eduardo Navas]: You describe your ongoing SPECFLIC project, currently in version 2.6, as “Distributed Social Cinema.” Given that your installation takes on so many aspects of contemporary media, could you elaborate on how you arrived at the parameters at play around this concept?

[Adriene Jenik]: SPECFLIC was initially inspired by the recognition that cinema was moving beyond a single fixed image at an expected scale to one of multiple co-existent screens with extreme shifts in scale. I was seeing video on miniature screens, as well as gigantic mega-screens, and seeing these screens move about in space and wondering what types of stories could take advantage of these formal and technological shifts. I’ve long been involved in thinking through layered story structures and at the beginning of SPECFLIC, I could “see” a diagram of the project imprinted on the inside of my eyelids. That original retinal image burn has since been honed and shaped in relation to the needs of the story and the responses of the audience and performers.

The SPECFLIC 2.6 installation takes excerpts from material that was created for SPECFLIC 2.0, and follows on the heels of SPECFLIC 2.5, which was commissioned by Betti-Sue Hertz and presented at the San Diego Museum of Art in Spring of 2008. For SPECFLIC 2.5, I stripped away all of the live, interactive aspects of the piece, and instead, emphasized aspects of the story that might have been more in the background of the live event. This type of “versioning” is something that is in evidence in software creation, but has also become a method for developing an art practice that can expand and embrace new research and technologies. Distributed Social Cinema is a form that takes into account the importance (for me) of the public audience for a film. As cinema-going practice becomes “home entertainment,” I’m interested in what is at stake in cinema as a public meeting space. At the same time, I’m playing with the intimacy of the very small screen, the ways in which having part of a story delivered into someone’s pocket adds a layer of meaning in its form of delivery. The SPECFLIC 2.5 installation was an attempt to consolidate some of these aspects of distributed attention and “voice.”

Granted the opportunity for networked interaction within the gallery@calit2, for SPECFLIC 2.6 I have rethought the installation to develop in concert with audience contributions. So the project is very much evolving in response to what I learn from each previous iteration as well as the opportunities afforded by the space, encounter with the audience, and technological framework.

[EN]: SPECFLIC 2.0 relies on science fiction to open a space for critical reflection. Would you share some of your influences?

[AJ]: Of course! The overall SPECFLIC project emerged as a result of an extended period of time where I had been gorging myself on works in the genre of “speculative fiction.” These works are generally understood to be more concerned with the “near future” or a future imaginable within the reader’s lifetime. They are less fantasy or prophesy than speculation. I sort of stumbled into this genre by way of the beautiful and frightening book “Parable of the Sower” by the recently departed Southern California writer Octavia Butler (1947-2006). This book challenged me to try and “tease out the threads” from my own present, imagining the future impact on even one or two generations of current trends I observed from my particular vantage point as a creative technology researcher at a top public research institution. Ever since reading the book when it was first published in 1995, I have been taken over by its poetics, scenes and storylines.

The work of Kim Stanley Robinson (in particular his early Southern California trilogy) provided encouraging notes of familiarity after I began crafting my own image of 2030 in Southern California. Canadian writers Nalo Hopkinson and Margaret Atwood, and British writer Daren King, have all inspired different aspects of this work. In particular, I have joined them in imagining (for better or worse) the future shifts in gender, class and race relations, which often form the basis of their stories. Chip (Samuel) Delaney’s enigmatic and profoundly kakographic novel Dhalgren, has continued to excite me with its parallel cityscape that exists as both a bubble and a hole.

I’m also deeply indebted to the Speculative Cinema enacted in Jean Luc Godard’s 1965 film Alphaville. I continue to delight in the ways that filmmaking practice can be used to create an imaginary future. Godard manages to create his vision of Alphaville within the Paris of the present and without special props, scenic design, costumes or effects, but solely through strategic use of the visual frame coupled with scripted language, precise gestures and thoughtful use of location shooting.

In every project, the writing of Brecht, Calvino, Borges and Stein seems to bubble up from the depths of my consciousness to assert its power anew.

Finally, I’m influenced by the education and research institution I inhabit. Entering the labs on campus and encountering the research of my peers can sometimes feel as if I am falling through a rabbit hole and emerging on the other side of the looking glass. SPECFLIC emerged from an overwhelming desire to try and understand where all of these research practices might lead. What types of stories emerge in a world where humans no longer omit odor? Where they control video games with brainwaves? Where diamonds are manufactured at will?

[EN]: One thing that comes to mind when I viewed SPECFLIC at the SD Museum of Art is the relationship of content and form. How do you think interfaces and devices used to access information are changing the way people think about knowledge? Do you see any similarities between music and text in this regard, meaning the dematerialization of the LP to the CD on to the MP3, and the book to the Kindle and other similar devices? In this sense it could be argued that music may be currently more successful than the text, if one considers success the amount of downloads of music files versus electronic books. Why do you think this might be the case?

[AJ]: I’m really hoping that this “collapsing” of content and form will result in this type of question about our interface to knowledge. There exists, within the flow of the network, all kinds of potentials and possibilities for expanded communication, experimentation and exchange. But contained within the technological framework that underlies this expansive, seemingly unbound flow is a level of exacting and precise control. The event itself is a public enactment of these dual tensions inherent in the move to an information society.

In terms of knowledge access, SPECFLIC 2.0 , 2.5 and 2.6 offer up a near future that is distinct from our near past in large part as a result of this shift in information access and knowledge acquisition. The InfoSpherian script and the images that play along the edges in the Library Story introduce a kind of nostalgia for the present. The serendipity offered within library stacks is both similar to, yet qualitatively different from losing oneself in a path of weblinks. In the stacks, color and size can attract one’s attention. And a misplaced item might end up on one’s stack. I parody my students’ incredulity at having to “read a whole book to understand its contents.” By having the story play out in a combination of large public displays and personal laptops and cell phones, I hope to create a space in which our everyday uses of these devices is denaturalized, so we can critically and publicly consider our own complicity in the dominance of the targeted search.

Regarding the similarities and differences between the digital production and distribution formats of music and text, I was thinking of this when I imagined the near future of the SPECFLIC 2.0 series. This is apparent in several instances, the first of which is that I do not believe that books will disappear. Rather, books as we know them now become the property of a niche category of people, similar to the function of vinyl now. There is an ongoing market and appreciation for vinyl, not just among collectors of old records, but music publishers regularly release special and valuable vinyl recordings. Sure, they are a bit of an anachronism, but they still exist and have not been completely wiped out and in some cases are even thriving.

In addition, the relationship between digital cultures and oral cultures has long been of interest to me. I observe in text chat a move away from strict textual literacy and toward a type of emerging “orality”. I’m interested in the increased sense of presence and “immediacy” afforded by an oral/aural communication system. In terms of the smooth transition to digital formats and distribution for music, there is also the issue of loss of audio fidelity vs. loss of visual resolution in the move to .mp3 (for sound) or computer screen (for text). We seem to have a much broader tolerance (audiophiles aside!) for a lesser quality in audio. Small shifts in sonic acuity do not affect our ability to concentrate on what we are hearing, nor do they instigate headaches. Furthermore, we can close our eyes when we listen to music or sound and the device itself disappears. When reading on the computer screen, the interface is always there in the foreground.

[EN]: In your installation, when the InfoSpherian comments that people read a whole book in the past, you also point to the idea of knowledge in terms of wholes vs. fragments. This moment of your installation exposed a personal struggle: I have often found myself focusing on specific chapters of books vs. the whole book for research purposes, and I often invest in the entire book at a later point, if possible. But even if I am not able to go back to the entire book, the fact that I physically come to access knowledge through a physical object does affect my relationship to accessing information in pieces. With data/information access via a network, I find that this sense is somewhat lost–dare I say, the guilt of seeing how much one has not accessed physically is no longer there, and the concept of rigor in research may be somewhat redefined. Am I wrong? Or do you think that this particularity will come to affect research at all levels for scholars, cultural writers and artists? If so, how?

[AJ]: Well, this is, of course, a core question regarding this shift from boundaried physical objects to networked entities. I continue to return to the importance of context (social, historical, philosophical) for grounding information or ideas, and the ways in which the “book object” (through not just additional chapters, but the organizing elements including the table of contents, index, footnotes, bibliography, etc.) give us a sense of a greater world of the book. This is a turn that not just evolves out of but reflects the values of the development of the information society. That shift, critically historicized by N. Katherine Hayles in her book How We Became Post-Human, hints at the ways in which the removal of matter from context to enable it to be treated as “data” or information allows for all kinds of engineering marvels. We are now experiencing, some 50-plus years after that shift, what a removal of information from its context might mean for society, scholarship, etc.

I will leave the effect on the concept of rigor in research to others (perhaps even yourself!).

But I would hope that future versions of the book (some of which can be glimpsed in the experiments and prototypes being developed by The Institute for the Future of the Book http://www.futureofthebook.org/) through incorporating a sense of the reading “commons” might involve even more “rigor.” I do notice my students are no longer as fixated on knowing the author or originator of a text or creator of an artwork. Perhaps this signals a move away from a sense of individual creation, and a movement toward an understanding of ideas arising from within a larger mix of voices?

But I continue to be occupied with the physical boundary of the book as an important signifier of time and space. The physical book object contains not just words and meaning, but an experience and even an historical marker for each reader. When I look at a book in my library, I remember a time when I read it, sometimes even the chair I sat in and the beverage I sipped. If I turn its pages, I see my notes, stains, creases; there is a visual memory of certain paragraphs or passages. When all of this shifts to the free flow of the InfoSphere; when e-books overtake physical books with their economics of storage, publishing and distribution; how do we “see” or reflect on what we have read and experienced? How do we continue to access that experience again and again with IP licenses set to timers? The whole point of the SPECFLIC project is that we really need a larger public to be wrestling with these questions — not just librarians or database programmers.

What’s exciting is to consider the relatively short history of the book itself and look at earlier versions of written communication (the scroll, the stone tablet) and understand the book object as we know it as just a point in a larger continuum of human communication.

[EN]: At one point in your installation, the InfoSpherian — which you explain is equivalent to the desk librarian — shows a book to the public. She describes the book as an object that in the year 2030 would be unfamiliar to the average visitor. The way that the InfoSpherian holds the book as she describes it reminds me of the constant preoccupation of the work of art as fetish, and the interest in its dematerialization. How is SPECFLIC reflecting on the ongoing changes in contemporary art practice, especially with the pervasiveness of information access today?

[AJ]: First, a note about the InfoSpherian: the character of the InfoSpherian is inspired by the position and placement of the Reference Desk Librarian. If you are in a library and have a question, you know you can go to the desk librarian and get help. In the live SPECFLIC 2.0 event, this was an important function of the character, as the audience could request information or particular books from the InfoSpherian, and these queries and her improvised responses contributed to the overall depth of the narrative performance.

Since SPECFLIC 2.5 and 2.6 were conceived as installations without this important layer of audience interaction, certain aspects of the InfoSpherian character were emphasized, and others de-emphasized or completely omitted. In the live 2.0 event, the character cycles through three distinct character “voices.” Each voice (and its accompanying changes in visual appearance and gesture) represented a different role that I see emerging as central to libraries as they grapple with their evolving social functions. These roles are a) interface to a material archive; b) Public Access Information filtering, licensing and enforcement (as information continues to grow exponentially); and c) Data Navigation Specialists, who will both assist the public and work behind the scenes as Information Scientists to conceptualize new ways of organizing and providing access to data.

So, to your question! The entire SPECFLIC project is meant to encourage public reflection and discussion and perhaps even heated debate about what we think about the cultural changes instigated by the move from analog (material) to digital (information/data). I design the projects with cross-generational audiences in mind, so that different ideas and attitudes toward these changes can be articulated not just by myself, but by those who encounter and participate in the work. So the InfoSpherian in SPECFLIC 2.5 and 2.6 enacts a sort of comic and (for some) dystopic future where the library and the book have almost completely de-materialized into the InfoSphere.

What remains is the “book object,” which as you note in your question takes on the form of a fetish; its objectness takes on increased value in certain contexts even as it loses its value completely in others. In the installation, I provide a platform for reflection in the form of book “stools” composed of books discarded by libraries. They are sculptures in their own right, constructed and positioned to afford stable, comfortable seating, even as they produce a slight discomfort among those of us who retain our attachment to the book object.

Larger issues of what remains to be seen or preserved are key questions (even dilemmas) for those of us engaged in producing, exhibiting and teaching art that is removed from a material context. I hope the project reflects my sense of historical flow — or the ways in which objects change their meaning and purpose over time. Someone might make a pot to hold water, or weave a basket to hold medicinal herbs, and later those objects might be encased in glass for us to behold as objects of great symmetry and craft. Discarded clothes become exalted quilts. Vacuum cleaners become sculpture. Books become stools. All of these objects retain residue of the past, but when bits become something else, there is no residue.

So, in a way, SPECFLIC is speculating not only about what happens in the future, but what happens to our past.

Lascia un commento

You must be logged in to post a comment.