The Elements of Selectivity: After-thoughts on Originality and Remix.

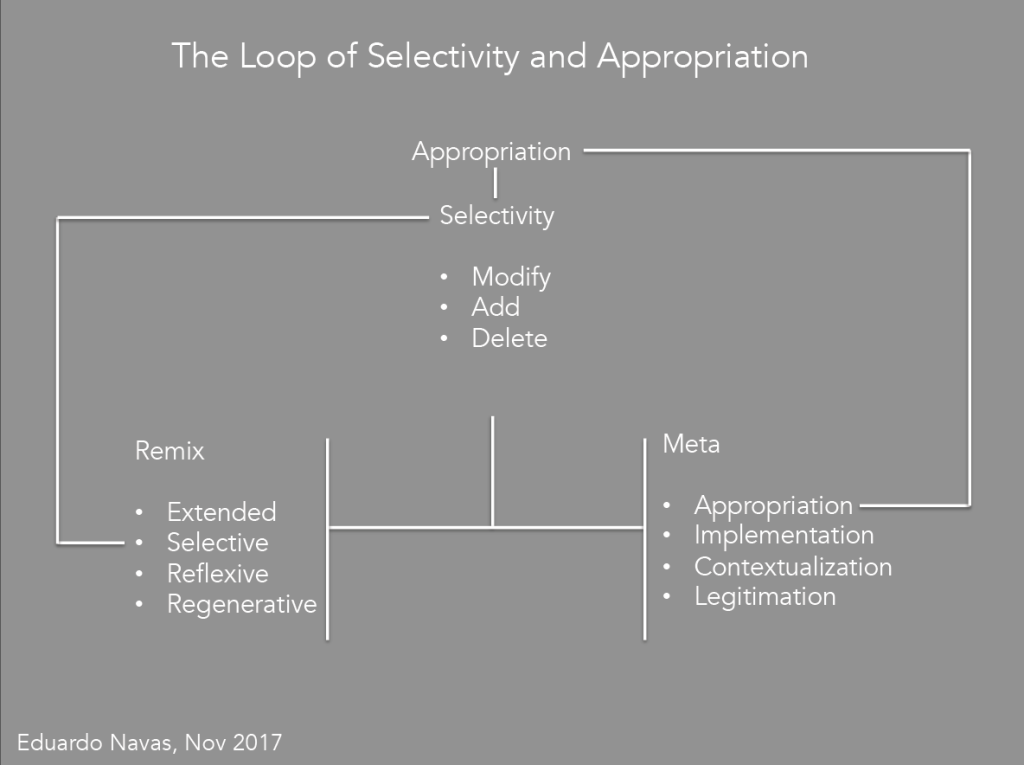

Figure 1: Diagram showing the tautological process of meaning creation.

The following are edited notes, which can be considered a theoretical mashup from a number of presentations which took place during the Fall of 2017, specifically on October 10 at the Arts & Design Research Incubator (ADRI), Penn State, on October 11 at The University of Caldas in Manizales Colombia, on November 1 at The University of Bern, Bern Switzerland, and as a lecture at Karen Keifer-Boyd’s graduate seminar class at Penn State on November 8. I was fortunate to have received ample feedback on what I presented, which led to the current set of notes I now share. I want to thank everyone who made my presentations possible, during what turned out to be a very busy, but intellectually fruitful period in 2017. In the lectures, I was able to explore the relation of the elements of selectivity (modify, add, delete) in relation to the cultural state of meta, which is the stage in which we create cultural value, and the different forms of remix. These notes, as is the case with much of my writing, are in the process of making their way in remixed fashion to different publications. In effect, the section titled, “The Elements of Meta” is already part of the closing chapter in my book Art, Media Design, and Postproduction: Open Guidelines on Appropriation and Remix (Routledge, 2018).

Challenges of Remix

When we think of remixing, most likely it is remixing byway of material sampling that comes to mind (taking a piece of an actual music recording). But remix principles are also at play in terms of cultural citation (making reference to an idea, or a style, story, etc). The difference between these two forms of recycling content and concepts can be noticed when examining the forms of the medley and the megamix. The medley is usually performed by a band, while a megamix is composed in the studio usually by a DJ producer, who understands how to manipulate breaks on the turntables.

When considering this difference and evaluating how sampling functions in the megamix (which is basically an extended mashup of many songs), it becomes evident that a remix in the strict sense of its foundational definition has to be materially grounded on a citation that can be quantified, in other words, measured because a remix is based on samples. While a sample is quantifiable, a cultural reference (citation) is not, and may not even be noticed by an audience, thus making the material performed appear original. Due to the ability to trace samples back to their sources, given that they are recordings, DJ producers quickly ran into trouble with copyright law: a lawyer could play a sample from a Hip Hop song, in direct juxtaposition with the source of the sample and prove on material grounds that the sample was an act of plagiarism.

[…]