Allegorical Remix, by Erwin Weishaupt

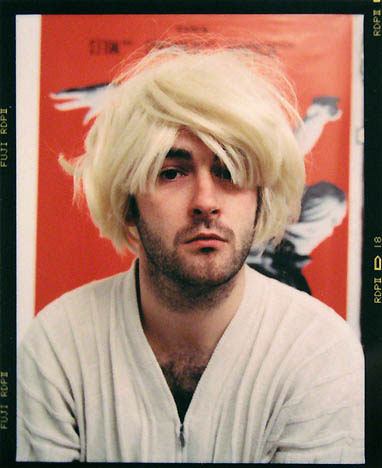

Douglas Gordon, Self-portrait as Kurt Cobain, as Andy Warhol, as Myra Hindley, as Marilyn Monroe (detail) 1996

Image and text source: artnet.com

“Douglas Gordon’s The Vanity of Allegory,” July 16-Sept. 10, 2005, at the Deutsche Guggenheim, Unter den Linden 13/15, 10117 Berlin, Germany.

Berlin’s creative world is so compartmentalized that you can be pretty sure you won’t bump into any of your fellow ravers at a museum opening, particularly at the Deutsche Guggenheim. Part of the global expansionist vision of the New York-based Guggenheim Museum, the single-room exhibition space, given a sanitary design by modernist architect Richard Glucksman and located unambiguously in the Deutsche Bank building on Unter der Linden, seems like a commercial box in the heart of a metropolis celebrated rather more for its underground art scene than for its institutional achievement in contemporary culture.

What to expect, then, in the way of progressive attitudes from a gallery inside a bank? On the one hand, the museum has given us notable exhibitions of works by Andreas Slominski, Bill Viola and Kasimir Malevitch. On the other, Deutsche Bank — a very conservative institution — is lobbying to destroy the soviet Palace der Republic on the city’s museum island and rebuild from the ground up the old Prussian royal palace (construction begins next month).

The exhibition “The Vanity of Allegory,” organized by the Scottish conceptual artist Douglas Gordon, did little to confound expectations. The show — “a self-portrait in the guise of a group exhibition” — brings together more than 30 works by artists who have previously shown at the museum, including Matthew Barney, Cerith Wyn Evans, Damien Hirst, Roni Horn, Jeff Koons, Robert Mapplethorpe and Lawrence Weiner.

Billed as an exploration of the self-portrait, vanity and the search for immortality, the show is designed to depict Gordon as something of a multiple personality by highlighting dialectical relationships between apparent opposites. For instance, Gordon’s own photographic portrait in masquerade as Kurt Cobain, Andy Warhol, Myra Hindley and Marilyn Monroe, arguably a self-deprecating gesture, is contrasted to the narcissistic power embodied in Jeff Koons’ glimmering stainless steel bust of Louis XIV from 1986.

Unfortunately, in the exhibition, the authoritarian guidance of museum politics seems to have pacified the artist’s playful iconoclasm. A certain lack of tension left the show feeling less like a meditation on vanitas than a mausoleum to ‘90s-era appreciation of Duchamp, Gober, Koons, Warhol and Gordon’s work itself. If the show is about proposing self-representation as a foolish attempt to deny the transience of life, it certainly manages to make such demonstration look like a cold and sterile death.

The most surprising element is an elaborately framed digital print of Pietro Perugino’s Bust of St. Sebastian. The State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg declined to lend the original, and Gordon’s gesture resulted in an oblique pun on the readymade, seriality and mass culture; ironically, the printout seemed the most contemporary of all the works in this shiny hall of fame. “Sampling” is central to Gordon’s artistic practice, as exemplified by his spectacular appropriated film installations (like his 1994 work 24-Hour Psycho, in which the Hitchcock film was slowed down to two frames per second and projected over an entire day).

Contemporary culture has all but abandoned the use of the term “appropriation” to describe this kind of borrowing and commentary. The recombinant (the bootleg, the remix, the mash-up) has become the characteristic pivot at the turn of our two centuries. We live at a peculiar juncture, one in which the original (an object) and the recombinant (a process) still, however briefly, coexist. But there seems little doubt as to the direction things are going.

Today’s audience isn’t looking at all — it’s participating. Half of the exhibition space has been converted in a cinema in which a selection of Gordon’s favorite cult movies, from Pasolini’s Theorema to The Legend of Leigh Bowery by Charles Atlas, are screened continuously.

Douglas Gordon’s persistent (dis-)location in Glasgow (and attendant Scottish accent) fits the provincial laissez-faire of our Prussian capital city, and his gold tooth and tattooed forearms seem more in tune with local subcultures than with the still-half-feudal code of corporate behaviour at Deutsche Bank. The joyful character of the artist drew its share of supporters. On the opening night, the partly mirrored exhibition space reflected Sylvie Fleury, in town to acknowledge the nonchalance of its fashion consciousness; Thomas Demand, in triumphant return from his conquest of America via the Museum of Modern Art; Tino Seghal, discussing the notion of “improvement” as it applies to his immaterial presentations; and Massimiliano Gioni and Ali Subotnick, the curators of the next Berlin Biennale, which some hope to see mounted once again in more alternative venues.

Nancy Spector, curator of the first Berlin Biennale in 1998, noted that several local artists — in keeping with Berlin’s contrary tradition — had refused to participate in this official exhibition. Today, it seems, the “avant-garde” is not a tribe of rebels as much as a set of tools and practices. So, the few skeptics who are still up for questioning fundamental assumptions about art could be found, after the Deutsche Guggenheim opening, at Berghain, Berlin’s “Turbine Hall” of electronica and dj remix.

ERWIN WEISHAUPT is a writer based in Berlin.

Lascia un commento

You must be logged in to post a comment.