“Regenerative Culture” by Eduardo Navas

«Information is not knowledge». (Albert Einstein). Linkedin maps data visualization. Picture: Luc Legay/Flickr. (see Norient for context)

Regenerative Knowledge was written between June and October 2015. It was published on Norient in five parts between March and June 2016. I want to thank Thomas Burkhalter and Theresa Beyer for editing the essay and making it available on Norient’s academic journal. In this essay I update the definitions of remix with an emphasis on the regenerative remix. I argue that constant updating is becoming ubiquitous, which is much more evident a year after the essay was written. A short version titled “Im/material Regeneration” was published in print as part of Seismographic Sounds in 2015.

Excerpt:

Introduction

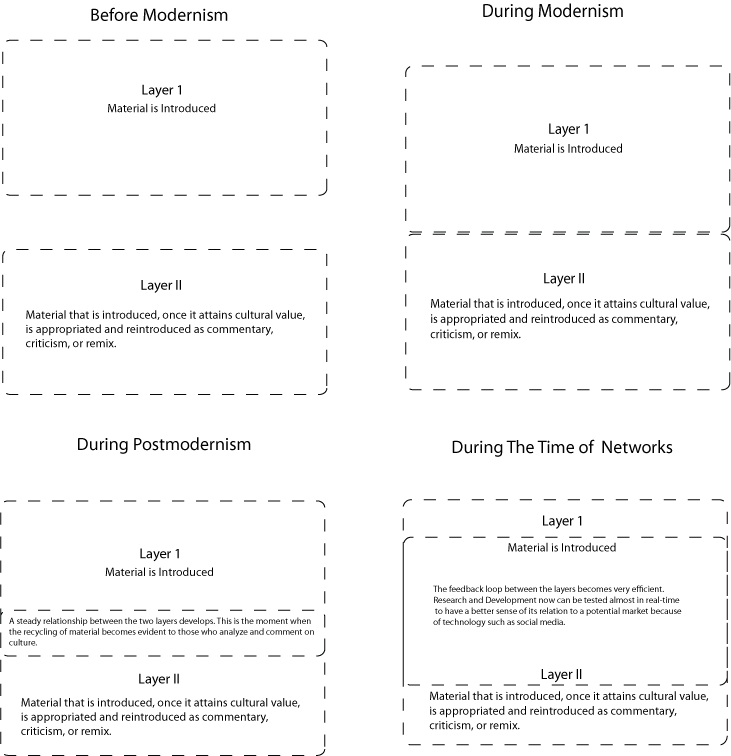

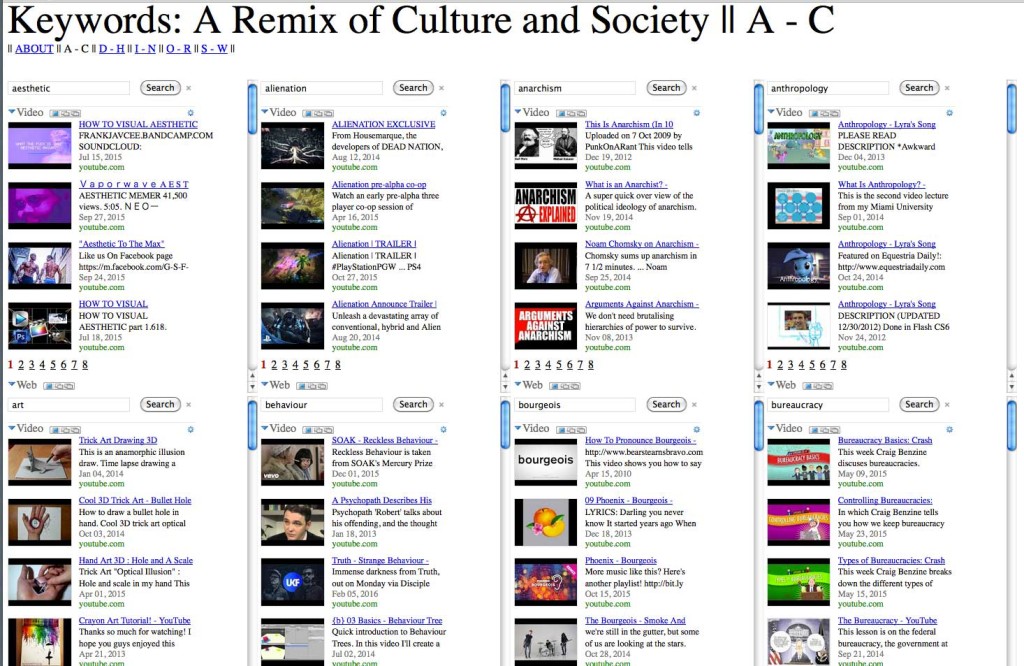

Cultural production has entered a stage in which archived digital material can potentially be used at will;[1] just like people combine words to create sentences (just like this sentence is written with a word-processing application), in contemporary times, people with the use of digital tools are able to create unique works made with splices of other pre-recorded materials, with the ubiquitous action of cut/copy & paste, and output them at an ever-increasing speed.[2] This is possible because what is digitally produced in art and music, for instance, once it becomes part of an archive, particularly a database, begins to function more like building blocks, optimized to be combined infinitely.[3] This state of affairs is actually at play in all areas of culture, and consequently is redefining the way we perceive the world and how we function as part of it. The implications of this in terms of how we think of creativity and its relation to the industry built around authorship are important to consider for a concrete understanding of the type of global culture we are becoming.

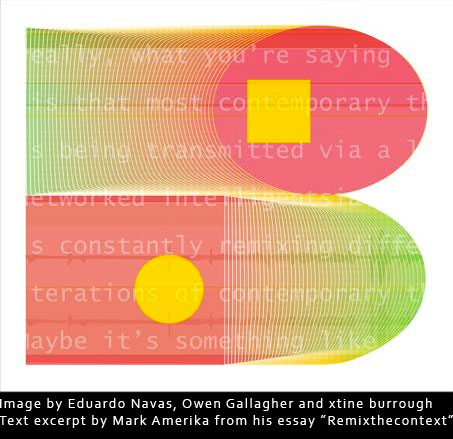

In what follows, I evaluate situations and social variables that are important for a critical reflection on how elements flow and are assembled according to diverse needs for expression of ideas and informational exchange. I begin by elaborating on what I previously defined as the regenerative remix,[4] which is specific to the time of networked media, to then relate it to speech in terms of sound and textual communication. I then provide examples that make evident the future trends already manifested in our times. Because digital media consists in large part in optimizing the manipulation of experience-based material that before mechanical reproduction went unrecorded, the aim of this analysis, in effect, is to evaluate how ephemerality is redefined when image, sound, and text are digitally produced and reproduced, and efficiently archived in databases in order to be used for diverse purposes. In other words, what happens when what in the past was only ephemeral is turned into an immaterial exchangeable element, and most often than not some type of commodity? To begin in what follows I analyze how the regenerative remix functions as a type of bridge to a future in which constant updates and pervasive connectivity will become ubiquitous in all aspects of life.

[1] This is a reasonable proposition as long as the person has access to the material. Some archives are evidently password protected. The person has to be also in a position to exert such an act, and this is linked to economics and class that define the person’s reality. I am not able to go into this issue in this text as its focus is on how sampling is functioning in terms of regeneration.

[2] This is already evident in the fact that the time it takes to produce just about any cultural apparatus has been shortened exponentially since the industrial revolution. Futurist Alvin Toffler makes a case with his term “The 800th Lifetime.” The much criticized Ray Kurzweil, who currently is affiliated with Google, also makes a case for exponential growth, arguing that Moore’s Law will be superseded in 2020, and we will enter a new paradigm of innovation. See, Alvin Toffler, “The 800th Lifetime,” Future Shock (New York: Bantam Books, 1970), 9-10. Ray Kurtzweil, “Ray Kurzweil Announced Singularity University,” Ted Talks, Last updated February 2009: https://www.ted.com/talks/ray_kurzweil_announces_singularity_university#t-188322.

[3] My use of the term “building blocks” is influenced by the work of Manuel De Landa, who discusses language in relation to biology and geology. I refer to his work throughout this essay. See Manuel De Landa“Linguistic History: 1000 – 1700 A.D.,” A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History (New York: Zone Books, 1997), 183 – 190.

[4] Eduardo Navas, “Remix[ing] Theory,” Remix Theory: The Aesthetics of Sampling (New York: Springer, 2012), 101-108.