Code Switching: Artists and Curators in Networked Culture, By Eduardo Navas

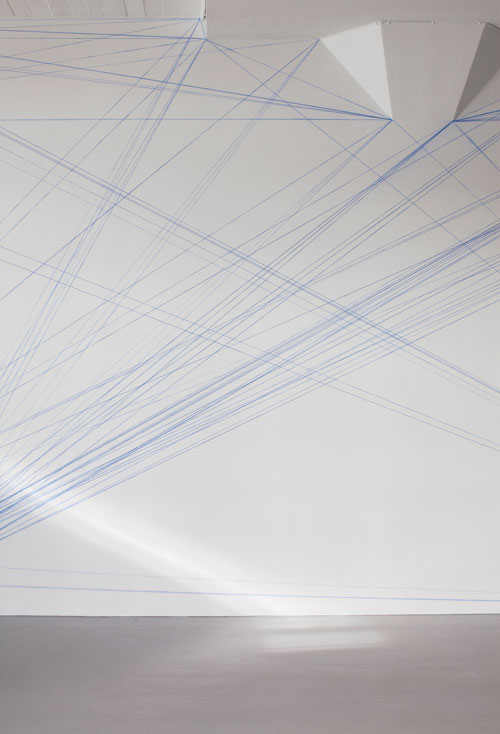

”Wall Drawing #51”, June 1970

All architectural points connected by straight lines. Blue snap lines.

Courtesy LeWitt Collection, Chester, CT

First installation in Sperone Gallery, Turin, Italy and Museo di Torino, Turin, Italy

First drawn by: P. Giacchi, A. Giamasco, G. Mosca

Image courtesy of Magasin 3

Read original post

Written for Swedish Traveling Exhibitions, December 2009/January 2010

Also published in R U International?, a yearly publication also by the Swedish Traveling Exhibitions, edited by Marten Janson and Sanna Svanberg, pages 90-105.

Note: The following text is the second of two originally published in the magazine Spana!, a publication for the Swedish Traveling Exhibitions (now called Swedish Exhibition Agency). I never got around to releasing the English version of the text until now. It reflects on the roles of artists and curators switching roles, influenced by conceptual art. It then relates such account to the overall experience I had when I visited the exhibition spaces and museums throughout Sweden.

The first essay is When the Action Leaves the Museum: New Approaches to the Exhibition as a Tool of Communication.

The list of previous posts that inform the two essays:

Sweden: October/November 2009

Notes on Sweden’s Approach to Art and Exhibitions:

Färgfabriken: https://remixtheory.net/?p=401

Interactive Institute: https://remixtheory.net/?p=402

Magasin 3: https://remixtheory.net/?p=403

Iaspis: https://remixtheory.net/?p=404

Mejan Labs: https://remixtheory.net/?p=405

Various Museums in Gothenburg: https://remixtheory.net/?p=406

During my travels as Correspondent in Residence for The Swedish Traveling Exhibitions during October and November of 2009, I visited museums and public institutions in Gothenburg and Stockholm that, in varying degrees, approach exhibitions as tools of communication. It became evident to me that their curatorial methods are sensitive to emerging trends in networked communication linked to the tradition of appropriation in the fine arts. In what follows, I examine how the use of appropriation as a tool of selection is part of curatorial and art practice, as well as exhibitions at large.

The Artist as Medium

Lucy Lippard, in her essay, “Escape Attempts,” reflects on her role as curator during the heyday of conceptual art in the 1970s. She quotes Peter Plagens’s review of her exhibition “557,087,” written for Artforum: “There is a total style to the show, a style so pervasive as to suggest that Lucy Lippard is in fact the artist and that her medium is other artists.” Lippard adds her own comment and elaborates, “of course a critic’s medium is always artists.”[1] It should be explained that Lippard was both critic and curator.

Lippard’s proposition resonates in New Media curating. In 2008, New Media curator Steve Dietz proposes that curators should stop thinking of themselves as “gatekeepers” and instead should rethink their roles as “creators of platforms that any artist who meets the articulated criteria can ‘join’ and build on.”[2] Dietz actually makes this argument while discussing an example of an artist run software online resource called Runme.org. Along these lines, Sarah Cook, another New Media curator, refers to curators as “facilitators and commissioners.”[3] Furthermore, Cook embraces the development of curatorial projects that recontextualize the exhibition space as a place of constant flux rather than of permanent display. She elaborates: “Curatorial practice has shifted in the past twenty to thirty years from museology to a more process-based methodology that focuses on temporary exhibitions and the specific context of their audiences.”[4] It is worth noting that Cook’s remarks move beyond New Media to curatorial practice across institutions, which is relevant to institutions I visited in Sweden.

New Media curators, such as Cook and Dietz, are quite sensitive to new exhibition approaches that redefine the curator’s role from arbitrator of culture to a type of collaborator that may at times borrow organizational strategies from artists. Their approach overlaps with Lippard’s philosophy on curating conceptual art during the seventies, as Lippard saw her role in conceptual art fairly open ended as well: “The times were chaotic and so were our lives. We have each invented our own history, and they don’t always mesh.”[5] New Media actually has gone through a similar process. The writings of curators such as Cook and Dietz are sensitive to the process of writing new media’s history, and at times they also do not mesh. Consequently, these three curators expose the interim role of the curator as artist, which has been a key element in the legitimation of New Media as a valid art practice. In what follows, I will explore in some detail the curator’s role when appropriating artistic strategies as well as its counterpart: artist as curator in New Media and its links to the fine arts, particularly conceptual art.

The Curator as Artist

Christiane Paul, the Adjunct New Media Curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, organized “CodeDoc,” in September 2002. For the exhibition, Paul provided twelve selected artists with instructions “to ‘connect and move three points in space.’”[6] The artists in turn took the instructions as a starting point to develop software art projects in which the code is put upfront in deconstructive fashion, so that online visitors are able to examine the creativity in writing code. The users then have the option of running the code to experience it visually. Keeping in mind Lippard’s understanding of the curator as a type of artist, in this case, Paul functions along the model of conceptual art; more specifically allegorizing the strategies of Sol Le Witt, who is well-known for writing instructions that are meant to be executed by other artists or museum employees. (We will return to Le Witt briefly.)

To be precise, I will focus on three of the artists who considered Paul’s instructions with drastic differences. Golan Levin interpreted three points in space in terms of global politics and created an interface that exposed economic ties between different countries. His contribution consists of the map of the world, where any three countries can be connected.[7] For example, if the user were to choose Mexico, Iraq and Venezuela, the software application would produce the following statement: “Axis of oil producing countries.” Mark Napier, another invited artist, created an interface in which three points are connected with green lines to create an abstract composition that can be adjusted by the user according to how she moves the triangular form, which constantly fluctuates on its axis, like an accordion.[8] The points leave an off-white trace of their travel on a grey background, as they move across the screen. Sawad Brooks, another participating artist, interprets Paul’s instructions by taking the html pages of three newspapers, the New York Times, the Guardian, and Asahi to combine them in one page.[9] The end result is an overwhelming amount of information that is unreadable, yet still carries a sense of authority due to the international recognition of the three newspapers. As is evident, the works in the exhibition are openly legitimated as creative responses to Paul’s proposition.

Paul here is acting along the lines of Lippard, who also argued “Critics are the original appropriators.”[10] To this effect, Paul herself is quite aware of the code switching between the artist and curator in new media practice. She actually reflects on curating as a tool for artists who develop projects to which participants can contribute according to pre-established parameters that, conceptually speaking, are not so different from her own instructions for CodeDoc:

…[A]rtists set parameters by means of software or a server and invite other artists to create ‘clients,’ which in and of themselves again constitute artworks. The initiating artist plays a role similar to that of a curator, and the collaboration often results from extensive discussions (sometimes on mailing lists established for the purpose).[11]

In both instances of artist as curator and curator as artist, the key element is feedback and communication. It is this element that new media shares with other institutions. All this is to say that the curator is no longer “curating” in the traditional sense, but more or less working like a conceptual artist, while the artist is extending conceptual art practice in New Media.

The Artist as Curator

Casey Reas is an artist who shares similarities with Paul. In June 2004, Reas in association with Jared Tarbel, Robert Hodgin, and William Ngan was commissioned also by Paul the collaborative exhibition “Software Structures,”[12] for which Reas literally took three basic Sol LeWitt drawing instructions and made adjustments to them in the form of software applications; each of his collaborators, in turn, reinterpreted the modified Le Witt instructions to write software applications of their own. The major difference in Reas’s work from Le Witt’s is that the software is designed to run on a loop until the user closes the browser window, while the algorithm (instructions) for LeWitt’s wall drawings have an end according to the final outcome that the artist foresees. Nevertheless, the computer executes the action in similar fashion to the person who executes LeWitt’s instructions.

During my Residency with the Swedish Traveling Exhibitions, I was reminded of the power of Le Witt’s drawing installations when I visited the artspace Magasin 3, located in Frihamnen (freeport), Stockholm. When viewing Le Witt’s work, the gallery visitor cannot help but be struck by the fact that the artists and gallery assistants who executed the instructions placed a great amount of creativity in the completion of the installations; yet, in a straightforward description of the process, they were mere executors of algorithms—similar to computers.

After having visited Magasin 3, I came to reconsider LeWitt’s basic algorithms to be even more relevant in new media practice than I first thought when I encountered Reas’s reinterpretation of Le Witt’s instructions. More importantly, the exhibition at Magasin 3 is a reminder for contemporary and new media art of the implementation of conceptual strategies by artists to produce art works as curators. To this effect it is worth noting that Le Witt was a contemporary of Lippard, as Reas is to Paul. The code switching between artists and curators, as it becomes evident at this point, is not new or particular to New Media. What is different, however, is that the sharing of methodological codes may no longer be expected but demanded in both fields of art production. How and why this happens in the first decades of the twenty first century needs to be evaluated.

Code Switching Between Artists and Curators

New Media art has its own specialized community; yet, the influence of the technology upon which it is defined has become embedded in various areas of culture throughout the world—certainly in direct relation to the exhibition as a medium of communication. This is possible because networked technology supports a new cultural attitude dependent on modular architecture, driven by the design of software and hardware to be swappable and to be used for multiple interests. The result is that the computer as a multitasking machine has a major influence both functionally as well as ideologically across disciplines, and enables people to take on multiple roles.

Multitasking enabled artists in the early stages of New Media to produce work and to also promote it individually or as part of group exhibitions. An example of this trend is the work of Alexei Shulgin, who in 1996 curated “Refresh,” an online exhibition in which any artist who wanted to join could contribute an online project of their choice to the exhibit. The projects were designed to be seen through automatic redirections (refresh) from page to page.[13] Note that here Shulgin is working as a curator, much along the lines that Paul describes, and which she also practices herself.

Another example from this early period of Internet art is the net art Latino database net which was curated between 2000 and 2005 by Brian Mackern. The online resource consists of a series of links from countries in Latin America in one page.[14] Mackern, like Shulgin, is an artist, who out of necessity to support new media work played the role of curator while developing his career as an artist. Arcangel Constatini is a Mexican artist who, at the time of this writing, is also the Curator of Rufino Tamayo’s Cyberlounge in Mexico City.[15] Similarly to Mackern and Shulgin, Constantini developed his practice with an awareness of the multiple roles artists had to play in the early stage of the new media field. And Gustavo Romano is an Argentine artist who also takes on the role of curator on a regular basis. He has produced several projects not only in Argentina, but also Spain. At the time of this writing he is curating a net art database for Museo Extremeno e Iberoamericano de Arte Contemporaneo (MEIAC) in Badajoz, Spain.[16]

In North London, England, artists Marc Garrett and Ruth Cathlow, who founded the online resource Furtherfield also administer HTTP gallery, where they have curated several new media exhibits since 2005.[17] Prior to this time period, in 1996, artist Mark Tribe founded Rhizome.org, a non-profit organization currently affiliated with the New Museum in New York.[18] And like all previously mentioned artists Tribe has curated exhibitions to legitimate new media practice in the arts.[19]

New Media inherited the tradition of artists taking the role of organizers or curators from previous art movements. In the seventies, again, conceptual artists not only in New York, but also throughout the world, as eloquently noted in the Exhibition Catalogue Global Conceptualism, edited by Luis Camnitzer, et. al., organized exhibitions that challenged exhibiting institutions at the time.[20] Some of the better known artists from South America that fall under this global trend are Lygia Clark and Helio Oiticica, who approached art as process, as a means to experiences. In their work the object was not necessarily dematerialized in the way that it was in New York conceptualism. This approach is similar to the philosophy of various institutions I visited in Sweden.

The recent tradition of artist as curator is now part of the international art market, as was acknowledged by Curator Jan Dubbaut during the Symposium, “Mountains of Butter, Lakes of Wine,” which took place at the Stadsteater, Stockholm on November 7, 2009. Dubbaut explained that artists who function as curators support a market driven art production as part of an international reconfiguration of funding for exhibitions.[21]

As the emphasis at this point has been deliberately on artists as curators, it becomes evident that artists are quick to reinvent their roles in order to share their work. Curators, however, are not able to claim openly a position as artists. They can only appropriate art strategies to develop innovative approaches for their curatorial practice. The reasons for this tendency cannot be fully entertained in the limited space of this publication, but a key element that can be evaluated briefly, which separates curators and artists as professionals, is that artists can move back and forth, and openly claim to be curators from time to time because the very foundation of modern art practice is based on such reposition as a gesture of resistance. One can go back to the 1850’s and notice that the French artist Gustave Courbet, when his painting The Studio of the Painter was not accepted to the “1855 Exhibition” in Paris, was quick “to curate” an exhibition of his single painting inside of a circus-like tent just across the official exhibition. Art historians consider this incident as a defining moment of the avant-garde.[22]

In contemporary curatorial practice, even after conceptual strategies as explored by Lippard are incorporated as valid conceptual tools to organize exhibitions, it is unlikely that curators would ever label themselves as both artists and curators, perhaps because they have always been appropriators, as Lippard noted. After all, the curator’s foundational methodology is to appropriate in order to care take, contextualize, organize and administer. Most recently curatorial practice, as is evident in this brief survey, was reconfigured along the lines of conceptualism; but certainly, curators are unable to produce actual work from “scratch” as artists can when desired. It is only after appropriation became commonplace in conceptual art practice that the roles of artists and curators came to share apparent methodologies.

The importance of the brief survey of code switching between artists and curators is worth consideration in relation to exhibitions at large because of two key elements mentioned by Cook and Paul respectively. As previously quoted, Cook argues that museums have adopted a process based approach to exhibitions in the last thirty years, while Paul when discussing the role of artists as curators emphasizes the importance of collaboration and discussion among artists and their support groups. At the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century, process, collaboration, and discussion are important elements in curatorial practice at large.

Conclusion: Code Switching in Exhibiting Institutions

In a previous text I wrote for the Swedish Traveling Exhibitions titled “When the Action Leaves the Museum: New Approaches to the Exhibition as a Tool of Communication,” I discussed the approach of various Swedish institutions to the exhibition as a medium of communication. One thing that became apparent in the philosophical mission of places such as the Museum of World Culture and the Maritime Museum in Gothenburg, as well as the art space Fargfabriken in Stockholm, and The Swedish Traveling Exhibitions in Visby among many others is that curators and administrators approach the public with a process based attitude, and the eagerness to create forms of feedback very much as defined by Cook and Paul.

The shift of exhibiting institutions from monolithic spaces to friendlier hybrid spaces that embrace the feedback from their audience is the result of the same new media technology that enabled artists to develop their own exhibitions. The general tendency in new media is for the viewer or participant, who for the most part had been passive prior to New Media, to become active by providing constant feedback. In the arts, as already noted, artists became pro-active at a fairly early stage of the Internet in creating their own models. Eventually, as access to the Web became commonplace, people grew accustomed to constantly opine; this was the norm at the end of the 1990’s with the growing popularity of group mailing lists, as well as the development of Web 2.0 in the early 2000’s, when blogs—and most recently—Facebook and Twitter evolved into the default forms of networked communication for the average online user.

Institutions like the ones I visited in Sweden obviously are sensitive to this shift. As noted in my previous article, The Museum of World Culture, for example, “wants to be an arena for discussion and reflection in which many and different voices will be heard.” This is really the same philosophy that led many artists in the early stage of the Web to develop list-serves for discussion among people who shared interests in the arts and its role in culture at large. Consequently, the curators at many of the institutions in Stockholm and Gothenburg that I visited did not see themselves as “gatekeepers” or “quality controllers,” but rather as facilitators and collaborators, much along the propositions of Cook, Dietz, and Paul.

In brief, the role of curators across institutions has been redefined. Curators have become selective appropriators who need to be invested in emerging social media to be able to develop relevant exhibitions because feedback, conversation, and constant communication are ubiquitous in global culture, proper.

[1] Lucy Lippard, “Escape Attempts,” Reconsidering the Object of Art: 1965 – 1975, ed. Ann Goldstein and Anne Rorimer (Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: 1996), 29.

[2] Steve Dietz, “Curating Net Art: A Field Guide,” Christane Paul, ed., New Media in the White Cube and Beyond (Berkley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2008), 78.

[3] Sarah Cook, “Immateriality and Its Discontents: An Overview of Main Models and Issues for Curating New Media,” Ibid, 32.

[4] Ibid, 29.

[5] Lippard, 18.

[6] Christiane Paul, curator, CodeDoc. September 2002, http://artport.whitney.org/exhibitions/index.shtml.

[7] Golan Levin, September 2002, http://artport.whitney.org/commissions/codedoc/levin.shtml.

[8] Mark Napier, September 2002, http://artport.whitney.org/commissions/codedoc/napier.shtml.

[9] Sawad Brooks, September 2002, http://artport.whitney.org/commissions/codedoc/brooks.shtml.

[10] Lippard.

[11] Christiane Paul, “Challenges for a Ubiquitous Museum,” New Media in the White Cube […], 65.

[12] http://artport.whitney.org/commissions/softwarestructures/

[13] http://sunsite.cs.msu.su/wwwart/refresh.htm

[14] http://netart.org.uy/latino/

[15] http://www.museotamayo.org/historial-cyberlounge/

[16] http://netescopio.meiac.es/

[18] For Tribe’s interdisciplinary activity see http://www.marktribe.net/

[19] For a good account on the history of early new media production, see Josephine Bosma, “Constructing Media Spaces: The novelty of net(worked) art was and is all about access and engagement,” Medie Kunts Netz, http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/themes/public_sphere_s/media_spaces/scroll/

[20] Luis Camnitzer, Jane Farver, Rachel Weiss, editors, Global Conceptualism (New York: Queens Museum of Art), 1999.

[21] For an evaluation of this and other relevant issues, see my essay “When the Action Leaves the Museum: New Approaches to the Exhibition as a Tool of Communication,” also written for The Swedish Traveling Exhibitions.

[22] This is a well-known historical moment that can be found in many modern art history books. For a detailed account which includes excerpts of letters and statements by Courbet, see Thomas Crow, et. al. Editors, “Courbet’s The Studio of the Painter,” Nineteenth Century Art: A Critical History (New York, Tames & Hudson), 236-237.