A Visit to Magasin 3: Notes on Sweden’s Approach to Art and Exhibitions, by Eduardo Navas

”Wall Drawing #715”, February 1993

On a black wall, pencil scribbles to maximum density. Pencil.

Courtesy Estate of Sol LeWitt

First installation: Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, MA

First drawn by: S. Abugov, S. Cathcart, A. Dittmer, F. Dittmer, L. Fan, C. Hejtmanek, S. Hellmuth, D.

Johnson, A. Moger, A. Myers, J. Noble, G. Reynolds, A. Ross, A. Sansotta, J. Wrobel. (Varnished by

John Hogan)

Image courtesy of Magasin 3

On November 5, as Correspondent in Residence for the Swedish Traveling Exhibitions, I visited Magasin 3, located in Frihamnen (freeport), Stockholm. Curator Tessa Praun took the time to discuss with me the history of the Konsthall (art space) which opened in 1987, and has since then developed an extensive collection of contemporary art.

In the tradition of appropriation, Magasin 3 takes its name after the building’s original function as a sea port storage facility. The space is hard to find, and one must make a definite commitment to visit it. I was no exception. I first took the subway then a bus to the end of the line, then walked and (as is probably common for first time visitors) got a bit lost, but finally found the space.

The Konsthall has a low-key facade, and retains the look of an industrial space. Its name is no different than the other storage facilities in the area (there are magasin 1, 2, 4, 5, and more); because of this, it is unlikely that a casual passerby will enter the premises. This exclusivity gives Magasin 3 an elegance defined with minimal aesthetics. Appropriately enough, at the time of my visit, the konsthall featured minimal drawing installations by Sol LeWitt, curated by Elisabeth Millqvist. The Sol LeWitt exhibition opened on October 2nd 2009 and will close June 6, 2010. In what follows, I discuss LeWitt’s work as well as two video installations by british based Israeli artist Smadar Dreyfus, curated by Tessa Praun.

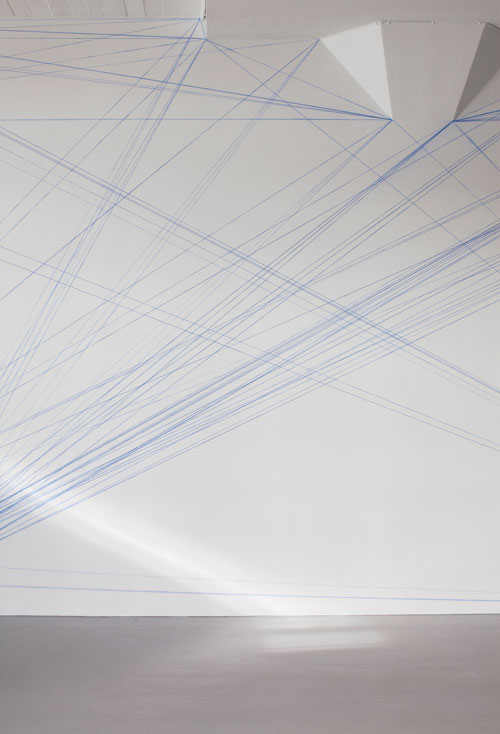

”Wall Drawing #51”, June 1970

All architectural points connected by straight lines. Blue snap lines.

Courtesy LeWitt Collection, Chester, CT

First installation in Sperone Gallery, Turin, Italy and Museo di Torino, Turin, Italy

First drawn by: P. Giacchi, A. Giamasco, G. Mosca

Image courtesy of Magasin 3

My approach in this entry will be a bit different from others in that I will compare LeWitt’s installation, “Seven Wall Drawings” at Magasin 3 with a project by Casey Reas, commissioned by the Whitney Museum of American Art. I find this to be fruitful because as it is commonly discussed in the new media field, there is a definite connection between new media and conceptual art. Further, I was able to experience an element of Remix when I visited Le Witt’s installation at Magasin 3.

”Wall Drawing #123”, 1972

Copied lines. The first drafter draws a not straight vertical line as long as possible. The second drafter draws a line next to the first one, trying to copy it. The third drafter does the same, as do as many drafters as possible. Then the first drafter, followed by the others, copies the last line drawn until both ends of the wall are reached. Pencil.

Courtesy Addison Gallery of American Art, Philips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts. 1991.20 gift of

the artist, Addison Art Drive

Image courtesy of Magasin 3

LeWitt is known for his instruction drawings. I had viewed a major exhibition of LeWitt at SFMOMA back in 2000, and was struck by how his instructions appeared rigid, but in their actual execution they offered a lot of freedom for interpretation. I was reminded of the power of his work when I visited Magasin 3. LeWitt’s wall drawings are essentially a set of algorithms that set in motion a process. While keeping this in mind, the gallery visitor cannot help but be struck by the fact that the individuals who executed the instructions at Magasin 3 put a lot of their creative drive into the completion of the installations; yet, in the end they were mere executors of algorithms. There is no question on who the author is in this case; but what resonates is how LeWitt questions the creative process. If we thought of him as a film director, the collaborative role of others in the realization of his vision would not be an issue, but being that LeWitt is an artist, the collaborative element of his work turns into a specific commentary on the artist as creator and/or executor.

This same issue resurfaced when computers began to be used creatively in the production of art. And for this reason I always thought of LeWitt’s work as a precedent to what takes place in computer applications: a set of instructions are executed according to the sensitivity of the programmer. This issue is best expressed in Software Structures by Casey Reas in association with Jared Tarbel, Robert Hodgin, and William Ngan.

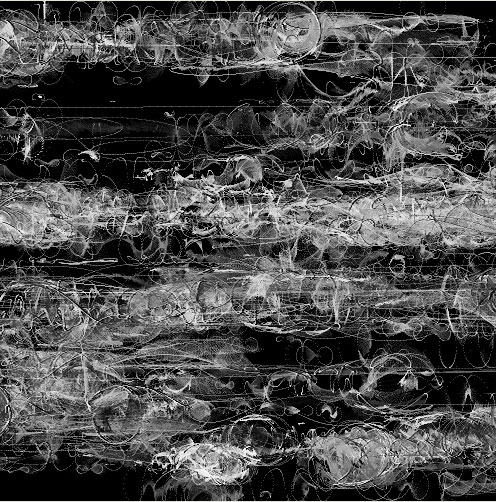

Image source: Whitney Artport

Software Structures

Structure #003B. Implemented by Jared Tarbell. Built with Processing

Software Structures is a cover, a version, an appropriation, a reinterpretation–a deliberate mashup of conceptual art and software art. This remix, however, takes effect not in material but in conceptual form (which can only be appropriate given that LeWitt is a conceptual artist). Reas literally took three basic LeWitt drawing instructions and made adjustments to them in the form of software applications. The major difference in the work is that the computer applications are time based, and never end–they will loop until the user closes the browser window. The algorithm for LeWitt’s wall drawings have an end according to the final outcome that the artist forsees. Nevertheless, the computer executes the action in similar fashion to the person who executes LeWitt’s instructions.

I had not seen a LeWitt installation since I experienced Reas’s software art project. After having visited Magasin 3, I find that LeWitt’s understanding of basic algorithms become even more relevant in new media practice. My hope would be that an exhibition of these and other works that share an algorithmic sensibility will be curated in the future. It would be worth a visit, even if one needs to get a bit lost to get to the space.

I should add that the installation of ”Wall Drawing #715”, February 1993, at Magasin 3 is quite striking for its obsessive character. The detail provided in the image at the top of this entry does not do justice to the drawing’s physical presence in the gallery space. The installation at Magasin 3 effectively offers the viewer evidence of obsessive labor as part of a collaborative process between executor and artist. I did not take away this sensibility from many of the works in the exhibition at SFMOMA (even though it was a while back, I do remember it vividly). Perhaps it may have to do with the Konsthall’s intimate yet impressive gallery space in contrast to the larger rooms of a major museum.

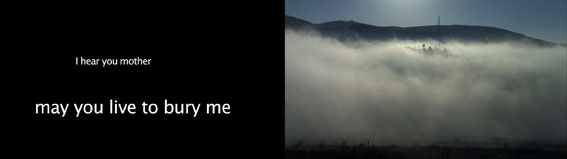

Mother’s Day, 2006–2008

Three channel HD video installation with six-channel audio

Duration: 15 min.

Directed by Smadar Dreyfus

Produced by Smadar Dreyfus and Lennaart van Oldenborgh

Developed in cooperation with Extra City Kunsthal Antwerpen

Still image

Courtesy: the artist

Image courtesy of Magasin 3

Another exhibit which I experienced at Magasin 3 is the work of Smadar Dreyfuss. The exhibition taking place from September 11 – December 13, 2009 consists of three video installations. I was particularly taken aback by “Mother’s Day” (2006-08), and “360 Degrees” (2007).

In July 1967, during the six day war, Druze Arabs on the Golan Heights were separated from their families on the Syrian side. Currently Druze university students from the area are allowed to go to Damascus in Syria to study, but cannot cross the line during the academic term. On Syrian mother’s day students and mothers stand across the line and shout, expressing their feelings for each other.

Dreyfuss, in the style she is known for, separates image and sound. “Mother’s Day” begins with a wide shot of Israeli-Syrian ceasefire-line in Golan Heights, then the screen goes black. A subtle cloud reminiscent of one seen in the introductory shot is still perceived, much like a visual echo. Voices are immediately heard shouting and translations in English appear on top of the cloud, with almost three-dimentional effect. Separating image from sound invites the viewer to consider the construction of experience through memory. This separation in effect turns into a metaphor of the reality that takes place across the ceasefire-line. The viewer is able to understand the separation lived in the Israeli-Syrian communities.

360 degrees, 2007

Single channel HD video with stereo sound

Duration: 26 min. 43 sec.

Directed and produced by Smadar Dreyfus and Lennaart van Oldenborgh

Still image

Courtesy: the artist

Image courtesy of Magasin 3

But Dreyfus does not always separate image from sound. Her work “360 Degrees” consists of a panoramic shot, slowly moving from left to right, of the Mediterranean beach located at the crux of Tel-Aviv and Jaffa. The area has a mixed Arab and Israeli population. Depending on when the viewer enters the installation, it is likely to have drastically different perceptions of the work. I first viewed the work when waitresses, mainly female, worked in the patio of a restaurant. I could not help but think of gender roles, as there were quite a few men in the scene. I decided to comeback at a later time, and when I did I encountered a very different scene of a beach. Here, the installation was more open for interpretation, as people were not as close to the camera as in the previous moment–and their roles could be read in multiple ways. I realized that the challenge posed by Dreyfus to the viewer with this work as well as Mother’s Day and others is to question personal experience, especially as the individual reconstructs it in the mind.

To see LeWitt and Dreyfuss in the same space was an unexpected treat. I was thrown back and forth between formal and ideological experience; and this I say not because the installations may be in opposition to each other, but because it is within the specific works that this tension takes place. In LeWitt’s one is pushed to think about the space in which the work is displayed, and given that his strategy in 2009 is of historical importance, it is possible to reflect on how his aesthetics may inform Dreyfus’s practice. Similarly to LeWitt, Dreyfus pushes the viewer to become aware of the mostly empty gallery space. This is especially true of Mother’s Day, where one feels as overwhelmed by the pitch black room as one is of Le Witt’s Wall Drawing #715.

This is not to say that these artists were deliberately shown at the same time for the reasons I propose here, but rather that it is inevitable to make comparisons when one experiences two minimal approaches in art making by two artists of different generations. Ultimately, the simultaneous exhibition of these works, and others I was not able to discuss in this entry, are a statement of the type of art which Magasin 3 is interested in supporting.