Step Away From the Sampler, by Peter Kirn

Image and text source: Key Board Mag

January 2005

Court rules all digital sampling illegal and the record industry objects — but you still have options

Get this: According to a fall 2004 ruling by the 6th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals, any use of a digital sample of a recording without a license is a violation of copyright, regardless of size or significance. In its decision in Bridgeport Music et al. vs. Dimension Films, the court said simply, “Get a license or do not sample. We do not see this as stifling creativity in any way.â€

“As far as sampling of recordings, they didn’t make it gray; they made it a line in the sand,†says Jay Cooper, a leading entertainment arts lawyer and a former president of the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (NARAS). Previously, courts had applied the question of size and significance to copyright infringement claims, but the new ruling changes that for sampling. Cooper says, “I think they went a little far afield from what the law has been in the past. Basically, the law has generally been there has to be more than a minimal use . . . this case basically said that you could take one note and that could be copyright infringement. They really did say that.â€

Nowhere to Run, Nowhere to Hide?

The case dealt with a three-note riff from George Clinton’s “Get Off Your Ass and Jam,†sampled by N.W.A. in their song “100 Miles and Runnin,’†which in turn appeared in the film I Got the Hook-Up by No Limit Films. The copyright owners, a music publisher and a recording label, sued the film company over a two-second sample of the Funkadelic original. It’s hard to even hear the sample in the finished N.W.A. song. But drawing an analogy to recent copyright legislation in Congress against music piracy, the court said that the very presence of digital sampling demonstrated infringement. Since the defendants don’t dispute that the riff was sampled, says the court, there’s no need to evaluate how large or small or recognizable the infringement was.

The decision makes a distinction between digital sampling and other forms of musical copying. Presumably, says the court, use of musical materials by a method other than digital sampling is still subject to what lawyers call a de minimis standard (Latin for “minimalâ€) in which amount and recognizability of the copied material must be considered. In other words, unless you’re using a recorded sample of the work itself, you can’t be sued for playing a Herbie Hancock lick on your CD, unless you’re copying a significant portion of his playing. For direct digital sampling, however, the ruling creates a new black-and-white “bright line†standard, which makes any copying of copyrighted material via digital sampling an infringement. The court says it doesn’t have the technical experience to rule on non-digital sampling, so it’s unclear whether using an analog tape recorder is permissible, but generally all sampling appears to be off-limits. If that’s too creatively limiting, the ruling advises, recreate a sample on a live instrument instead of using a sample of the original recording.

Does the decision go too far? The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) thinks so. In an amicus briefing, the RIAA argues that the appeals court decision is unprecedented and unsustainable, and unfairly treats digital recordings as different from other copyright issues. Sampling cases, says the RIAA, should continue to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, applying the de minimis standard to determine whether an infringement is significant enough to be worth judicial consideration.

So why is the RIAA, a staunch defender of strict copyright law in its battle with music piracy, arguing in this case for flexibility in the law? Simple: as a representative for recording labels, the RIAA must be concerned about a legal precedent that is too broad, resulting in extensive, expensive litigation. Making matters worse, the appeals court decision doesn’t even have its facts straight: the decision makes a blatant, fundamental error about copyright law, claiming that recorded material dating from before 1972 is unprotected.

Even Robert Sullivan of Loeb & Loeb, who argued the case for the plaintiffs, agrees that the court’s rigid sampling rule would lead to more litigation. “You do kind of open the floodgates; instead of simplifying with a bright line test,†he says. “You have to bring in expert witnesses to tell you is the sample there, is it a replay.†Neither the defendants nor the plaintiffs had argued that the de minimis standard should be eliminated.

Dimension Films is appealing the case, though for the time being the ruling is the law in the sixth district and a new decision isn’t expected any time soon.

Keeping Your Work Legal, For Fee or Free

Legal wrangling over this decision aside, Cooper’s advice to musicians sampling is simple: Get a license. “We all know that the unauthorized use of a sample in a new creative work is illegal,†says Cooper. “Is it three notes or four notes? There’s never been a ruling that says how many notes. As an example, if you were to use the first four notes of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 — if it had been composed and recorded recently, that is — it would clearly be copyright infringement.†While this case would eliminate any gray area for digital sampling, Cooper and others associated with the case all agreed on one piece of advice for musicians: Don’t take any chances. Using samples in your music, or using any other musical materials, means you’re creating a ‘derivative work’ from someone else’s work. If there’s any question, get permission.

Of course, many musicians find the process of licensing samples expensive and complex. The hip-hop community used sampling as a creative tool, and then paid dearly when copyright infringement caught up with the music. Moby religiously licenses the samples he uses in his music, even though it can take an enormous amount of time and effort just to track down the owner, much less negotiate a fee.

Backers of free licenses say they have an alternative for musicians that’s completely legal, but cost-free, offering an opportunity to follow the law without stifling creativity. “If you believe in a world where people are able to sample each other’s stuff, vote for it — use a Creative Commons license on your work,†says Creative Commons Assistant Director Neeru Paharia.

If you have an audio track you’d like to let other people post freely or sample, Creative Commons (www.creativecommons.org) provides licenses that allow you to protect your copyright ownership while allowing people to make derivative works, stipulating whether you only want to allow non-commercial use, or commercial use, among many other options. Paharia says that with crediting options, which require derivative works to give you full recognition, the licenses can be used as a means of disseminating music and promoting your work. Using Creative Commons’ search engine, you can look for openly-licensed audio and other media, as well as make sure your work can be found by others. You won’t find anything by George Clinton or N.W.A., but you will find an emerging community of musicians sharing their creations — possibly the wave of the future for legal music sampling.

Creative Commons doesn’t oppose copyright law; the licenses simply allow you to choose how your work is used within the copyright law. “Our only goal is to give people more options,†says Paharia. “Keeping things open enables us to build on each other’s content, which enables us to move culture and creativity forward.†DJ Spooky and Roger McGuinn have embraced public domain sources of content in their work, for instance, while Gilberto Gil, David Byrne, the Beastie Boys, and many others have released recordings with sampling licenses for people to remix and use in their work.

Whether the license is free or for fee, whether you want to share your work as a means of promoting your music through Creative Commons or profit by others sampling through licensing, you’ll want to know the law. Whatever the result of the sampling decision ultimately is, sampled work will certainly remain protected by copyright.

Get Off Your Ass and Sue

How in the world does a guitar part laid down in 1975 get to be at ground zero ot the intellectual property debate in the new millennium? Get your notebook out and see if you can follow this.

Fig.1 Funkadelic’s Lst’s take it to the Stage

N.W.A. sampled two seconds of a guitar riff from Funkadelic’s “Get Off Your Ass and Jam†from Let’s Take It to the Stage (Westbound, released 1975), Figure 1.

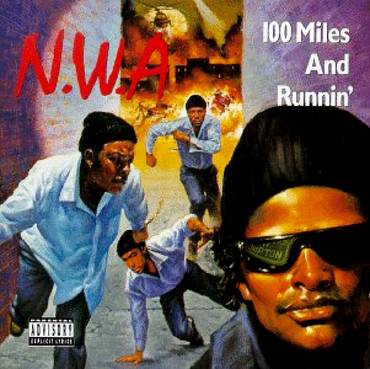

Fig.2 NWA 100 Miles and Running

N.W.A. used the sample in its song “100 Miles and Runnin’†on 100 Miles and Runnin’ (Ruthless, released 1990), Figure 2.

Fig.3 I Got The Hook-Up

The George Clinton original was cleared for use in that song, along with more easily recognizable samples such as The Supremes’ “Nowhere to Run.†But the N.W.A. song didn’t have “sync†clearance for the song’s samples to be used in movies, so while No Limit Films’ movie I Got the Hook-Up (Figure 3)got hooked up with the rights for “100 Miles,†it lacked sync rights for the George Clinton sample — hence the lawsuit by the Funkadelic song’s owners.

Lascia un commento

You must be logged in to post a comment.