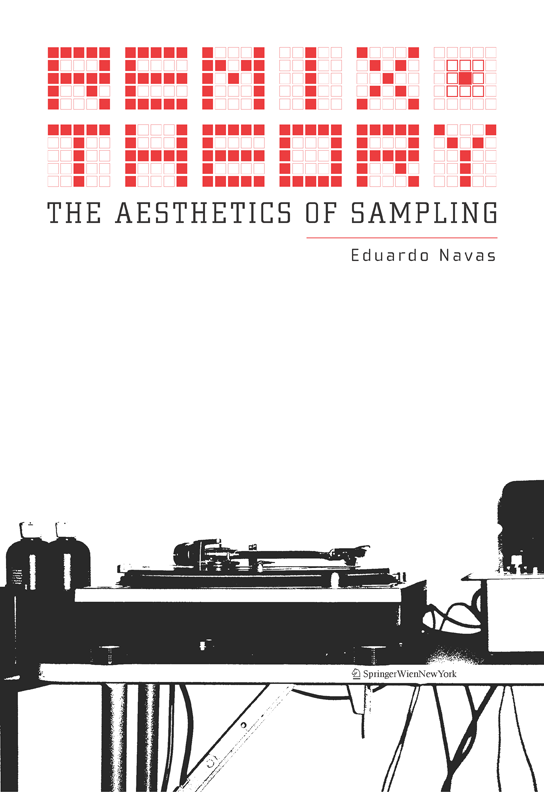

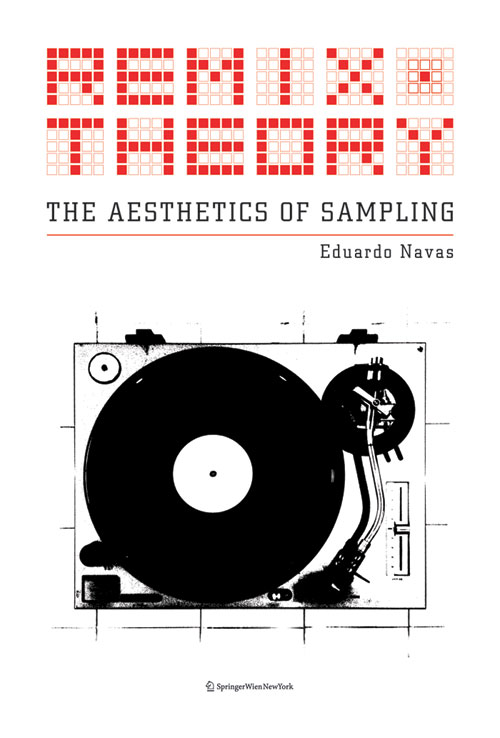

Pre-order Remix Theory: The Aesthetics of Sampling

Cover Design: Ludmil Trenkov

Remix Theory: The Aesthetics of Sampling can now be pre-ordered. You can place your order on Amazon, Barnes and Nobles, Powell’sl Books, or another major online bookseller in your region, anywhere in the world. The book is scheduled to be available in Europe in July, 2012 and in the U.S. in September/October of 2012.

The book will also be available electronically through university libraries that have subscriptions with Springer’s online service, Springerlink. I encourage educators who find the book as a whole, or in part, of use for classes to consider the latter option to make the material available to students at an affordable price.

Anyone should be able to preview book chapters on Springerlink once the book is released everywhere. If you would like a print copy for review, please send me, Eduardo Navas, an e-mail with your information and motivation for requesting a print version.

For all questions, please feel free to contact me at eduardo_at_navasse_dot_net.

Also, see the main entry on this book for the table of content and more information.

Below are selected excerpts from the book:

From Chapter One, Remix[ing] Sampling, page 11:

Before Remix is defined specifically in the late 1960s and ‘70s, it is necessary to trace its cultural development, which will clarify how Remix is informed by modernism and postmodernism at the beginning of the twenty-first century. For this reason, my aim in this chapter is to contextualize Remix’s theoretical framework. This will be done in two parts. The first consists of the three stages of mechanical reproduction, which set the ground for sampling to rise as a meta-activity in the second half of the twentieth century. The three stages are presented with the aim to understand how people engage with mechanical reproduction as media becomes more accessible for manipulation. […]The three stages are then linked to four stages of Remix, which overlap the second and third stage of mechanical reproduction.

From Chapter two, Remix[ing] Music, page 61:

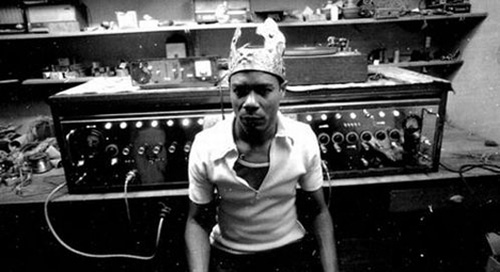

To remix is to compose, and dub was the first stage where this possibility was seen not as an act that promoted genius, but as an act that questioned authorship, creativity, originality, and the economics that supported the discourse behind these terms as stable cultural forms. […] Repetition becomes the privileged mode of production, in which preexisting material is recycled towards new forms of representation. The potential behind this paradigm shift would not become evident until the second stage of Remix in New York City, where the principles explored in dub were further explored in what today is known as turntablism: the looping of small sections of records to create new beats—instrumental loops, on top of which MCs and rappers would freestyle, improvising rhymes. […]

From Chapter Three, Remix[ing] Theory, page 125:

Once the concept of sampling, as understood in music during the ‘70s and ‘80s, was introduced as an activity directly linked to remixing different elements beyond music (and eventually evolved into an influential discourse), appropriation and recycling as concepts changed at the beginning of the twenty-first century; they cannot be considered on the same terms prior to the development of machines specifically design for remixing. This would be equivalent to trying to understand the world in terms of representation prior to the photo camera. Once a specific technology is introduced it eventually develops a discourse that helps to shape cultural anxieties. Remix has done and is currently doing this to concepts of appropriation. Remix has changed how we look at the production of material in terms of combinations. This is what enables Remix to become an aesthetic, a discourse that, like a virus, can move through any cultural area and be progressive and regressive depending on the intentions of the people implementing its principles.

More excerpts available once the book is available.